We’ve Never Needed Sci-Fi More

How writing, film, and music allow us to escape our current realities.

I’m still reeling from my first trip to Japan. Among many unforgettable experiences, to see Tokyo all lit up at night, up close and personal, triggered something deep in my Gen X sci-fi nerd soul. For someone who’s grown up on Blade Runner, William Gibson and 2000AD, the neon sprawl and kanji characters are kind of like a musical chord that echoes throughout every idea of what “the future” was meant to be.

It still looks like the future, too, no matter how much of a cliché it may have become. But the strange thing is, if you look closer there’s an awful lot of what feels like anachronism. Alongside the bright lights, slick infrastructure and gigabit wifi, there’s a lot of make-do-and-mend, a lot of home-laminated handwritten signs, gaffer tape, fax machines, CDs: technologies that serve a specific purpose perfectly well, so why would you replace them? Add to that the ubiquity of older traditions still – the street corner shrines, folk figurines, celebrations of the cherry trees – and, to dazed Western eyes at least, it feels like a constant flux of past, present and future all at once.

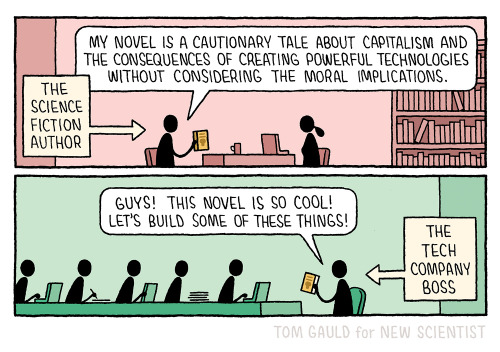

This came soon after Protein had asked me to put some thoughts down based on a conversation I’d started in SEED CLUB, titled We’ve Never Needed Sci-fi More. It had been prompted by frustration that tech bros like Thiel, Bezos and, most egregiously, Elon Musk were claiming to be inspired by science fiction, but appeared to be profoundly misreading what they most wanted to champion. That’s not a new observation, indeed it’s already become a truism via the likes of Tom Gauld’s New Scientist cartoon, and Alex Blechman’s “we have created the Torment Nexus” tweet from 2021.

But the sci-fi failings of the broligarchs is not just in their building of dystopias, which they’d likely be doing whatever they read. There’s something deeper in, for example, Musk’s inability to see the communitarian message of Iain M. Banks or the absurdist satire of egotism in Douglas Adams that suggests a) he’s engaged about as deeply with those texts as he has with the video games he gets other people to play for him, and b) we who love those and other great sci-fi works need to be shouting about their qualities from the rooftops.

As others in SEED CLUB were quick to point out, there’s sci-fi, and then there’s sci-fi. There’s subversive stuff that prepares us for the present moment, like the mighty Octavia Butler (who wrote about LA wildfires and predicted a violent “Make America Great Again” president back in the 1990s) or Doris Lessing, or the ribald satire of Judge Dredd or Transmetropolitan. There’s “hopepunk” and “solarpunk”, subgenres explicitly aimed at imagining better, sustainable futures, which have entire communities dedicated to them. But there’s also plenty that plays into the stereotypes: phallic rockets, Great Men on heroic adventures, technological leaps forward and all the other tropes that appeal to ambitious and domineering child-men. And spectacle sells: witness how Villeneuve’s noisy, crass take on Dune hit the mainstream, while bona fide modern sci-fi masterpieces on TV, like The Expanse and William Gibson adaptation The Peripheral, remain cult favourites.

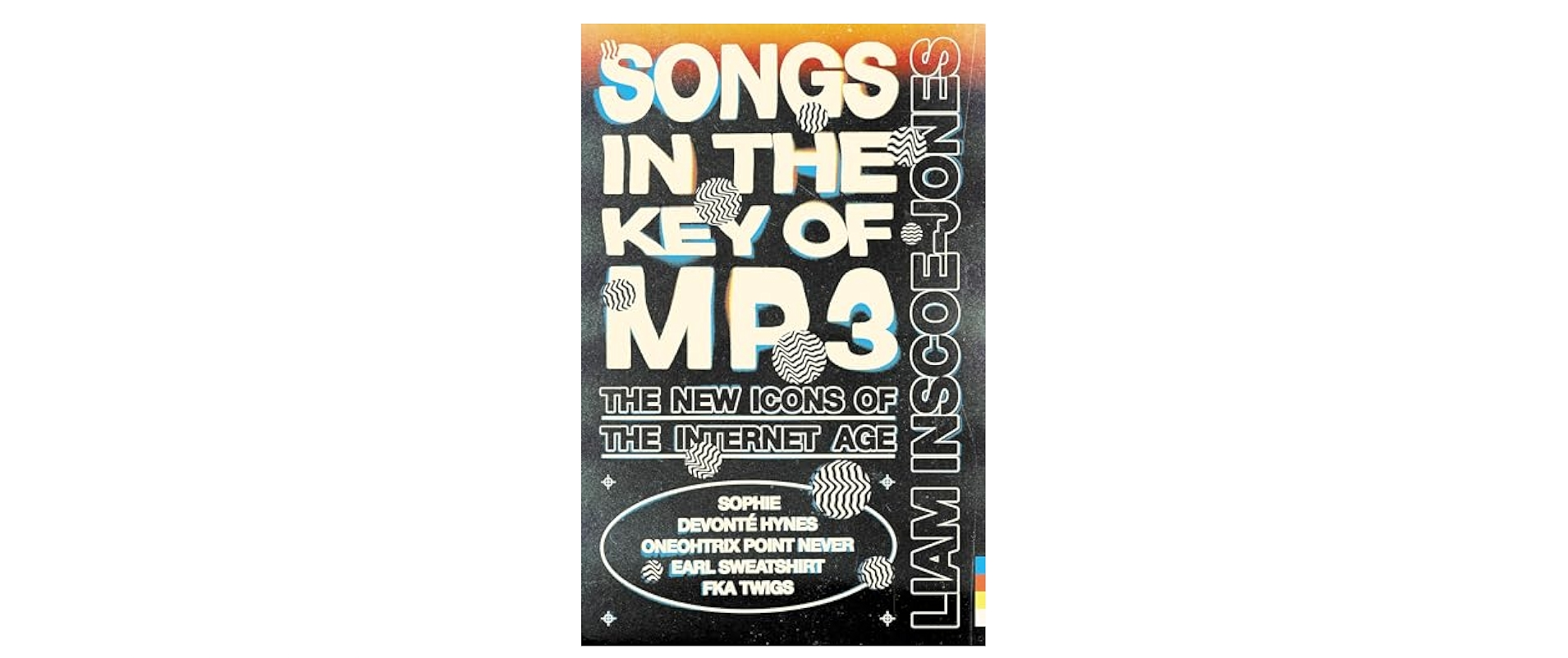

As I mulled all this over, I thought too of music. Having had a 1990s adolescence I came of age bathed in techno, drum’n’bass, Autechre; I avidly absorbed Kodwo Eshun’s conception of musical works as “sonic fictions” in their own right, and wondered where that focused sense of futuristic vision had gone as genre melted down in the glut of availability of the 21st century. I knew progress and a sense of dreaming of the future hadn’t disappeared but it became much less tangible in the flux. Then, on my flight to Japan, I read a new book, Songs in the Key of MP3 by Liam Inscoe-Jones, which traces the lives and influences of influential contemporary artists: Devonté Hynes (of Blood Orange), FKA Twigs, Oneohtrix Point Never, Earl Sweatshirt and SOPHIE.

This book covers a lot of ground, but a key thing it keeps coming back to is how these artists mine familiar tropes of the past as a kind of “unfinished business”, and create new presents – and, yes, futures – from this. So not only do SOPHIE and Oneohtrix Point Never inject explicitly sci-fi, avant garde tropes into the pop mainstream but they, and the other artists, are in fact doing imaginative futurist dreaming as radical as anything 4Hero or Carl Craig did in the 1990s.

With this swimming around my head as I wandered through the technological, seemingly-anachronistic collage of Tokyo, I thought of how actual fiction can perform a similar function. William Gibson once said: “The future is already here – it’s just unevenly distributed.” “When you cut into the present,” said William S. Burroughs a few years before, “the future leaks out.” And when I once asked the eternally creative musician Georgia Anne Muldrow about the concept of Afrofuturism, she responded:

“My only thing is I’m an ultra-present African, I strive to be ultra-present. With time, I think a lot of things can get misconstrued with the title ‘Afrofuturism’ as far as what the aims of it is: but it’s a dealing with time itself, knowing we been here so long, and I really believe in the past, present and future merging into one thing. That comes out in my sound, in how I talk to people, in my sense of humour: the whole spectrum of Black people throughout time. It’s not just in the future, it’s happening right now. All we’ve ever had is right now, moment to moment. I’m into technology: my job title is that I’m an instrument of the ancestors, and I work with computers, so that’s really Afrofuturist.

But that was really happening naturally before that title gained more traction for naming things and labelling them and shipping them off. Which is cool: that’s allowed me to be a guest on college courses, I’ve had great experience in what this is as a philosophy, and it’s beautiful that this is something that’s of value to academia or the like. But when you zoom out, academia has a far way to go in the values that it holds for children, for people who seek to gain knowledge. Some of the values it holds are very flawed and very colonial. So when it comes to Afrofuturism, it’s cool that people can name it this, that or the third, but it’s always been happening, it’s just another name for us living, for Black folks just be. We talk and we talk, we been in the past, present and the future, so I say ‘that’s just how we be’: it’s different to ‘that’s just how we are’.”

So yes, we have never needed sci-fi more, but there’s a lot to unpick. Perhaps the modern term “speculative fiction” is better, because it offers a broader view of how we use the imagination to conjure where technology might go or what it could have done – but however we approach it we should be thinking about how writing, film, music and art allow us to time travel, not just forwards, but backwards, sideways and diagonally at the same time.

It’s about broadening our minds so we can hold space for all that at once. And to do that, what we need above all else is sci-fi literacy: an understanding of it as an unfolding culture, with a past, present and future of its own.

Or to quote two other great minds who sprang back to mind as I was strolling the streets of Tokyo, blinded by the lights:

“Science fiction is held in low regard as a branch of literature, and perhaps it deserves this critical contempt. But if we view it as a kind of sociology of the future, rather than as literature, science fiction has immense value as a mind-stretching force for the creation of the habit of anticipation. Our children should be studying Arthur C. Clarke, William Tenn, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury and Robert Sheckley, not because these writers can tell them about rocket ships and time machines but, more important, because they can lead young minds through an imaginative exploration of the jungle of political, social, psychological and ethical issues that will confront these children as adults” – Alvin Toffler

“The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent” – Ursula K LeGuin

| SEED | #8312 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 22.04.25 |

| PLANTED BY | JOE MUGGS |

Discussion