"The avalanche, in Washington’s Cascades in February, slid past some trees and rocks, like ocean swells around a ship’s prow. Others it captured and added to its violent load. Somewhere inside, it also carried people.”

These are among the gripping opening sentences of the New York Times’s interactive story Snow Fall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek. The 2012 story of an avalanche that killed five skiers in Washington State, the six-part feature took more than six months to produce and successfully wove together text, graphics, video and photography. It was viewed by more than three million people in the first few weeks after it was published.

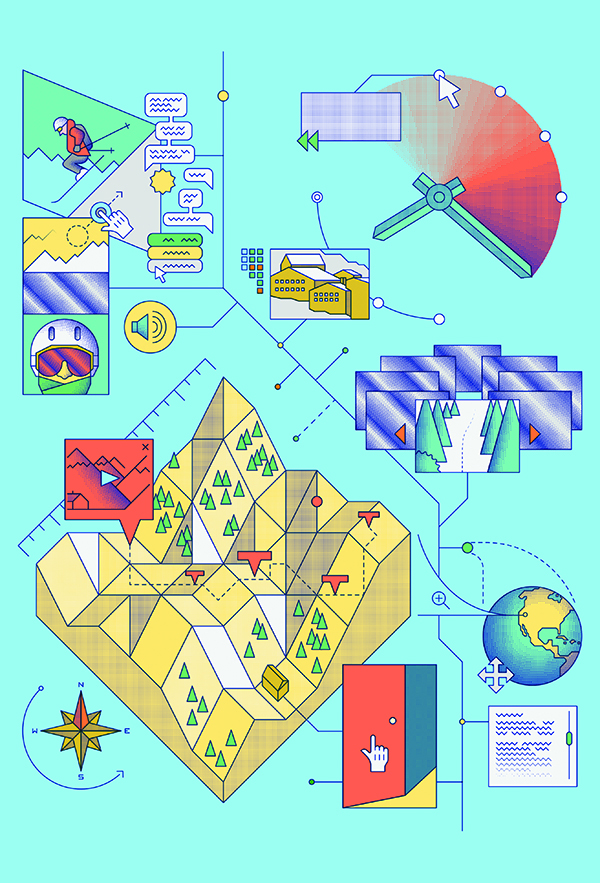

The journalist behind Snow Fall, John Branch, won a Pulitzer prize for his engaging account of the incident. The way in which the story was told, a presentation of words and pictures that went beyond a linear format, has seen it become a much-quoted, oft-admired benchmark for digital-age storytelling. Post-Snow Fall, many new mediums are shifting control over to readers and viewers with experimental new formats. News stories, music videos, and even traditional books are all receiving interactive adaptations.

The band Arcade Fire has invited interaction using all manner of devices for music videos, created under the direction of film-maker Vincent Morisset (featured in Protein Journal#11). Reflektor, for instance, let the viewer cast a virtual projection on the screen by holding their mobile phone up in front of it. The National Film Board of Canada’s Bear 71, described as a “fully immersive, multi-platform experience”, enables viewers to explore the world of a grizzly bear via augmented reality, webcams, geolocation tracking, motion sensors, a microsite, social media channels and a real bear trap. The iPad version of The Waste Land zooms up close on the famous T S Eliot poem, using performances from famous actors, video of Seamus Heaney discussing crucial passages, and a host of other interactive devices to help elucidate a sometimes impenetrable poem.

According to Janet H Murray, interaction designer and author of Inventing the Medium, these slices of interactive storytelling are examples of how the media landscape is changing forever. Each gives users the opportunity to get as involved in the story as they want to – skimming over the top or drilling down into detail as the fancy takes them. They all deliver an enriching complexity to already compelling stories. “The author is still in control, but the audience has agency – they can choose how deeply they want to get involved,” says Murray. “The story is not non-linear; it still works as a story. But it is multi-sequential, and you can choose how you navigate through it. That is what we mean by interactive storytelling.”

Why is interactivity emerging now? One reason is change in attention spans. In the past five years, our attention spans have altered dramatically – both upwards and downwards. YouTube ads are now cut back to 15 seconds to avoid audiences punching the dreaded Skip Ad button – yet “binge-watching” has been added to the Oxford English Dictionary to describe lengthy viewings of multiple episodes of shows such as House of Cards on Netflix. “There is now a broad spectrum of attention,” says Matt Locke, who runs Storythings, an agency that specialises in interactive storytelling. This means the competition for our viewing attention is higher than ever, and marketers, directors and media channels alike are having to work harder to attract it; an elaborate and engaging viewing experience makes an offering stand out.

There has also been an important shift in the entertainment industry. For instance, in 2013, the Grammy Awards altered the Best Long Form Video category to Best Music Film, recognising the film-maker’s contribution and the documentary component of the new interactive music videos. Online music channel Vevo similarly gives credit to directors, while new awards such as the YouTube Awards turn the spotlight onto emerging film talents based online. When the talent behind new digital mediums is recognised, people are further encouraged to experiment with them.

Another factor driving interactivity is that new technology devices have acquainted almost everyone with the idea of participation – pledging, tapping, touching, tweeting. We are all getting involved in the media and culture we consume, reading with our right hand poised over the keyboard or smartphone. (Writer David Hepworth recently likened writing online content to trying to talk to someone who has their hand on the door knob, always ready to move on.) Social media, meanwhile, has become the primary means of mass distribution and circulation of stories.

Within a few minutes, feedback had reached McCall, who was addressing the audience at home – telling them off for cheating One consequence of this direct participation is a host of new insights about audience attention, behaviour and context. These help storytellers to create stories – and business models – that dovetail perfectly with what their audiences want when they consume media. For Locke, storytelling is now about “knowing your audience like never before, understanding what they want to do with your story and facilitating that.”

This gives storytellers new inspiration. The Walking Dead video game is synchronised with each new season of its corresponding TV show, and focuses on story and character development rather than puzzle-solving or shoot ‘em ups. The dialogue and actions of the characters lead to changes in the game. The choices made by the player carry over from episode to episode and are tracked by the video game company to help them write further episodes. The game has won 90 different awards since it was released in early 2012 and has sold over eight million copies.

Audience behaviour can also inform and transform live television broadcasts. Quiz show The Million Pound Drop Live on Channel 4 uses real-time data from hundreds of thousands of online players to feed stats and observations to host Davina McCall. When one question referred to the Paddy Power website, online players rushed there to get the answer, creating a spike in traffic that crashed the site. Within a few minutes, feedback had reached McCall, who was addressing the audience at home – telling them off for cheating.

This invitation to the audience to participate actively in the culture they consume seems new, says Locke. “From 1950 to 2000 was an incredibly stable and, to be honest, quite weird period where people consumed culture from mass-distribution networks where the role of the audience was very, very small,” he says. “When writer and director Richard Curtis (Notting Hill, Four Weddings And A Funeral) was writing the UK sitcom Blackadder back in 1981, the production team didn’t even get sent audience ratings, so they had no idea of the show’s reception. Curtis took to walking the streets of Shepherd’s Bush in London, looking in people’s windows to see if they were watching the show, and if they were laughing.”

But stories like this can be misleading. The truth is that the post-war period was an anomaly, argues Locke, when – for various technical reasons – the audience went quiet. Further back into the past, the picture changes. In 19th-century supper clubs, for example, members of the audience would actually get on stage and perform. “It has gone back to that today,” says Locke. “The audience insist on getting involved.”

But will the audience always wish to play a part? Surely many of us will continue to read print books and other stories without any kind of participation. Some of us don’t wish to play director and would rather sit back and enjoy the entertainment. Today’s children, many of whom regularly consume interactive media, may be a good indicator of the future. Consider, for instance, that 40% of primary schools in the UK use iPads and as many as 54% of kids in the US are reading ebooks. Many of these contain content such as images, animations, games and puzzles that go beyond a beginning-middle-end narrative.

Jack and the Beanstalk was recently transformed into an interactive gamified app by children’s publisher Nosy Crow. Readers helped Jack to complete tasks in order to get him down the beanstalk. “This is something that great children’s books like Where’s Spot? and The Very Hungry Caterpillar have done for young children for decades, but technology makes it possible to take playfulness further,” commented Kate Wilson, Nosy Crow’s managing director, in a Guardian article about the future of digital publishing.

Janet H Murray can easily imagine a future where complex stories such as Game of Thrones are told using the techniques of interactive storytelling being pioneered today. “Interactive storytelling will allow people to more actively follow the story, even play some small part in the action. You could be a Lannister or a wildling! You could have parallel adventures that would reflect the TV series.” Would people really want to do that? Absolutely, says Murray. “We all like make-believe,” she says. “We identify with fictional characters and fictional worlds. Stories satisfy us in deep psychological ways. Make-believe is very appealing.” Illustration by Alex J Walker