Universal Everything

We meet Matt Pyke, the driving force behind one of Britain's most exciting digital design studios

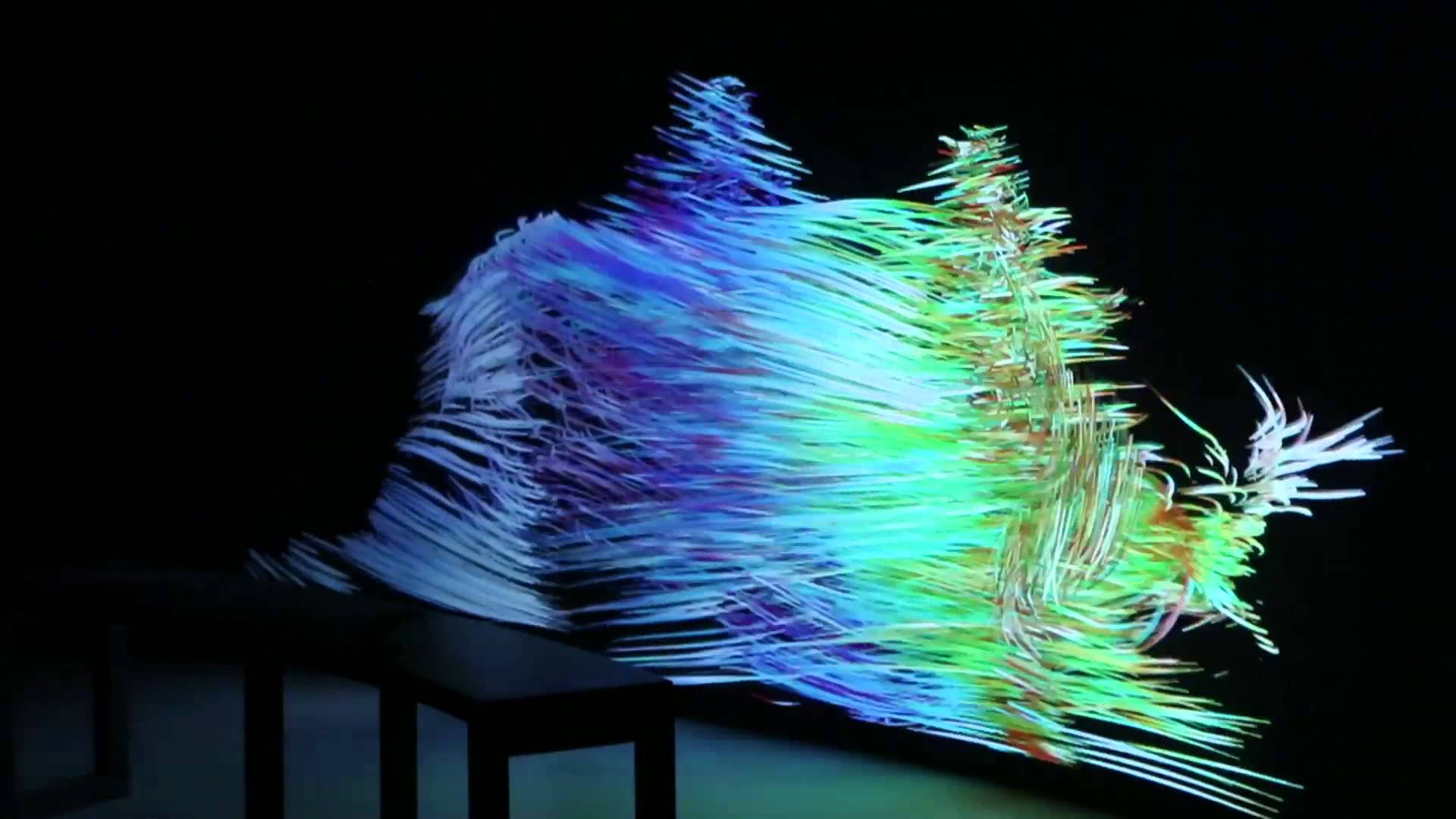

British digital design studio Universal Everything has created installations in the world’s largest cities and works for clients that range from luxury brand Chanel to new York’s Museum of Modern Art. Much of the studio’s work exists at the boundary of new technology. Its takeover of Hyundai’s Vision Hall in South Korea contained a video wall that was 25 metres high and four metres wide, the highest-resolution screen in the world, with 36-channel surround sound. Walking City, a digital animation and homage to sixties architectural collective Archigram, depicts a female figure striding purposefully as her form slowly evolves from one abstract design to another. So you might assume that Universal Everything is based in London – perhaps inside a huge modern co-creation space in the heart of the city’s start-up district of Shoreditch. But the studio isn’t based in a co-creation space. It isn’t even in London. Universal Everything, founded by Matt Pyke, is housed in a small log cabin just a stone’s throw from the Peak District national park near Sheffield. Before this it was in even humbler surroundings: Pyke’s own attic.

Pyke originally relocated to this part of the country in 1996 after accepting a job at The Designers Republic, the studio best known for creating Warp Records’ album artwork. Eight years later, he left and set up Universal Everything, drawing on the combined talents of friends in the industry and his brother Simon, a musician who recently released an EP on Warp to coincide with the <Universal Everything & You – Drawing in Motion> exhibition at the Science Museum. Ten years on, while the studio’s creations have become grander and more unexpected, the scale of the operation and the team behind it have barely changed. “I love Sheffield because there aren’t too many distractions,” explains Pyke. “There aren’t that many people in my industry up here, and none of the clients or galleries that I work with. There’s a nice thing that Matisse once said when he moved to Tahiti – I think he stole it off someone else. He said he wanted to be in competition with himself only.”

Being removed from the London set also offers a fresh perspective. Small local communities of creativity, such as London’s Shoreditch, can offer an agglomerative advantage for small agencies, but can also suffer from producing clichéd styles and trends. Often it’s a case of too many people trying the same thing. Working on a global scale not only avoids this, but creates an entirely new signature style. “There’s a lot of debate about migration into the cities because it seems more economical,” says Pyke. “When I started out, moving to London was the obvious goal, but working in Sheffield has its perks. Because I had to speak to people over the internet, it forced the sort of remote global studio set-up that we have. We’ve got programmers in Japan and America, musicians in Germany and animators in Siberia rather than just a guy down the road in Shoreditch. The whole world is a potential talent pool.”

This same fresh perspective has helped the Pyke brothers develop an independent approach to working with clients. When a brand commissions a creative, now a regular occurrence in the arts, the brand can sometimes over-direct and over-control the relationship. But Universal Everything don’t compromise. “We don’t have any intense conversations with branding departments,” says Pyke. “They tend to give us a few ingredients and leave us to it, much like our work for galleries or museums. Our influence is intended to give the brand a bit more freedom, flow and emotion.”

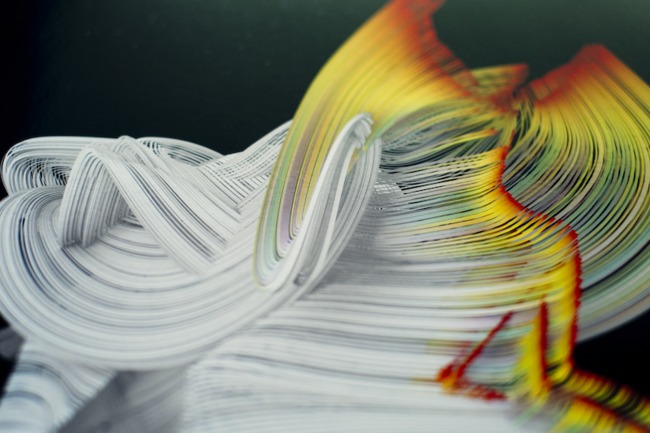

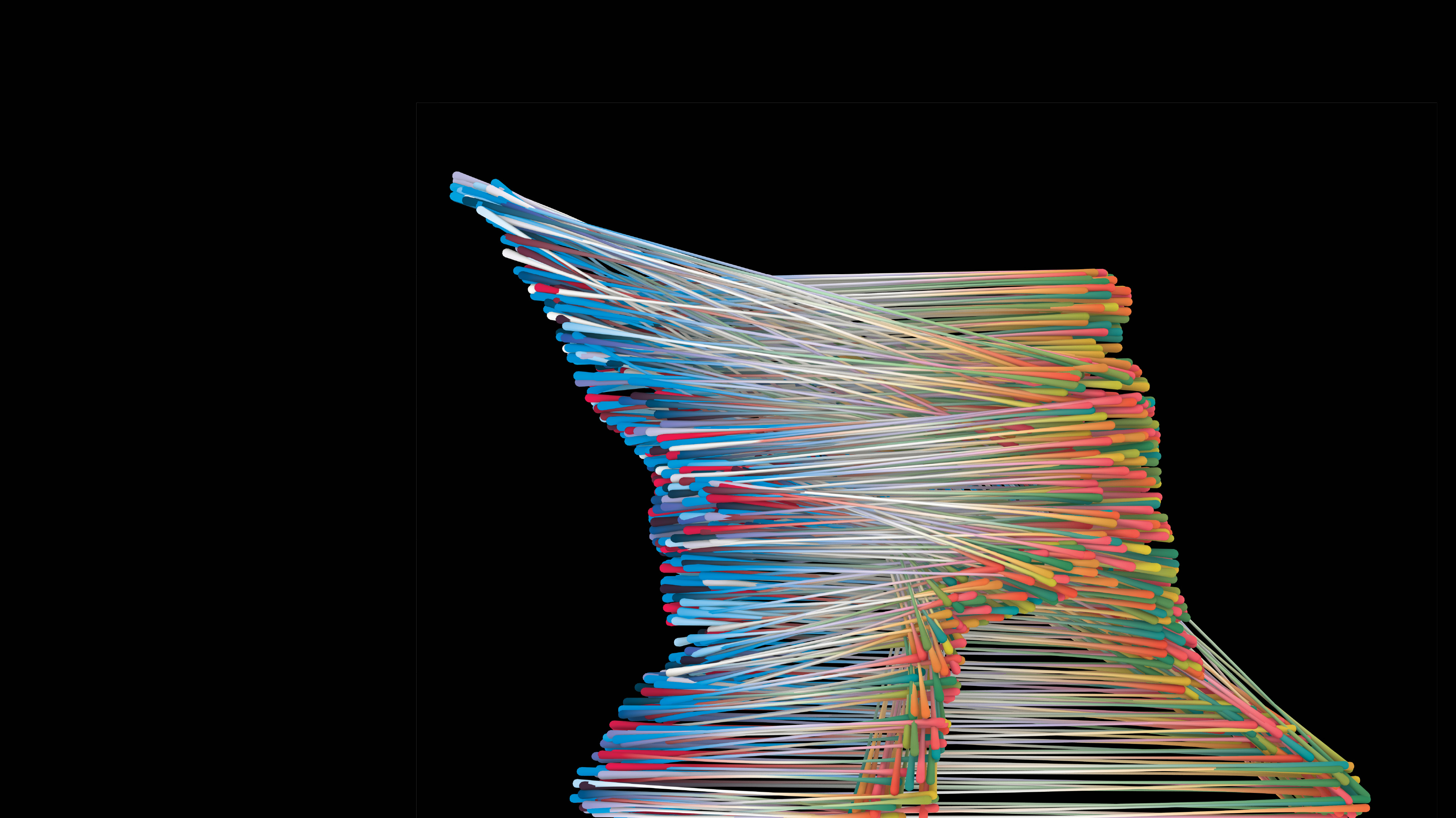

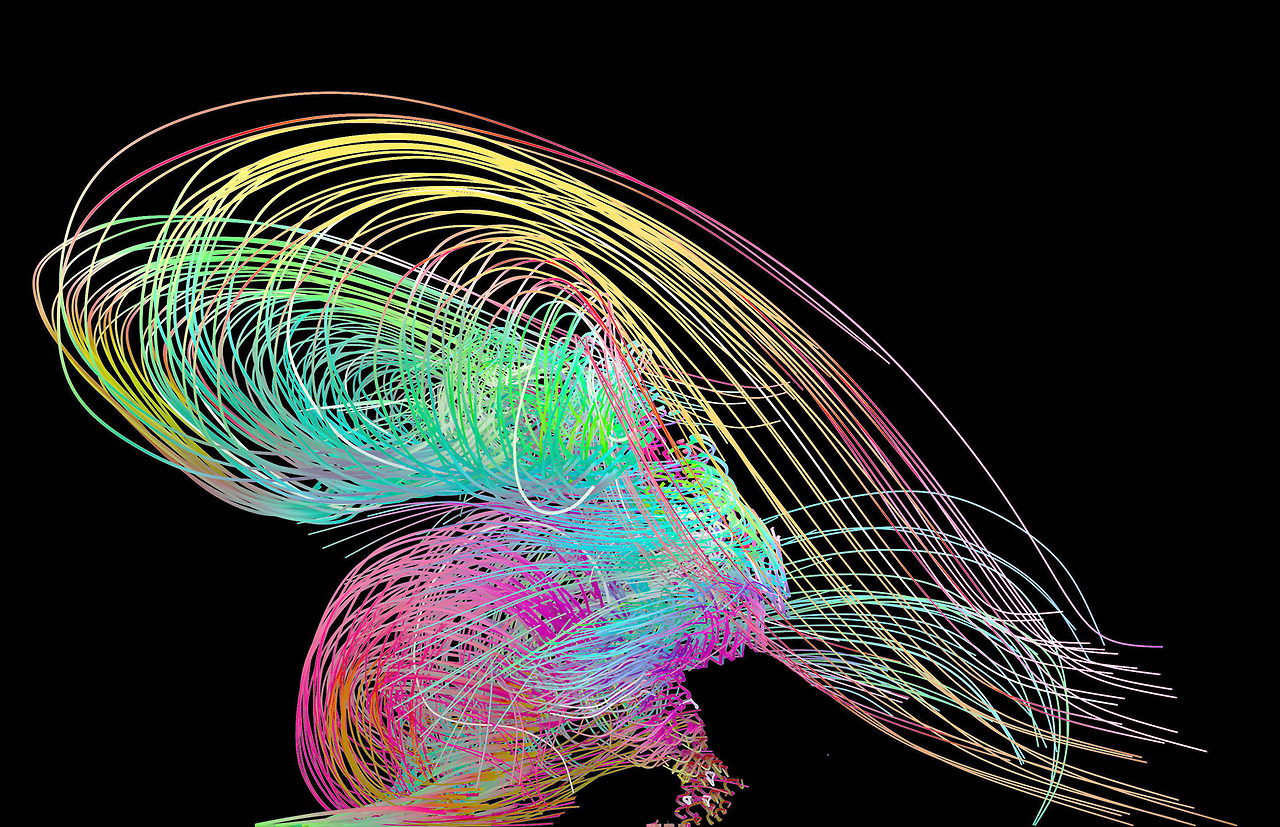

The studio’s rambling northern surroundings, along with Pyke’s history in architectural and botanical illustration, have had a noticeable influence on Universal Everything’s work. “The patterns and behaviours and geometry that occur in nature have crept into what we do,” explains Pyke. “There are a lot of similarities between the malleability and organic nature of code and the way nature works in terms of its simple DNA or artistic instructions. Technology and nature meet quite happily.” The union of living things and technology has become Universal Everything’s signature approach. While the studio is not based in an urban landscape, most of its creations are, breaking up the atmosphere of a built-up environment using works that reference the elements, or plant-like and people-like forms. “The most important thing for us when working with technology is that it has a very human, emotional quality. That’s more important than technology showing off,” says Pyke. “There should always be a level of authenticity and reality. Sometimes we push it with technology to see how much soul we need, but as soon as you push it too far, it breaks.”

As if to demonstrate his commitment to reality, Pyke starts each project by drawing his ideas using pen and paper. He’s adamant, however, that technology is not to be feared and can be just as creative, if not more so. “Technology actually expands our potential. You can create your own tools, which are far more powerful and individual than existing ones. Many beautiful things have been made with a piano or a pencil but when you create your own tools or your own software, that’s when you start finding your own voice.”

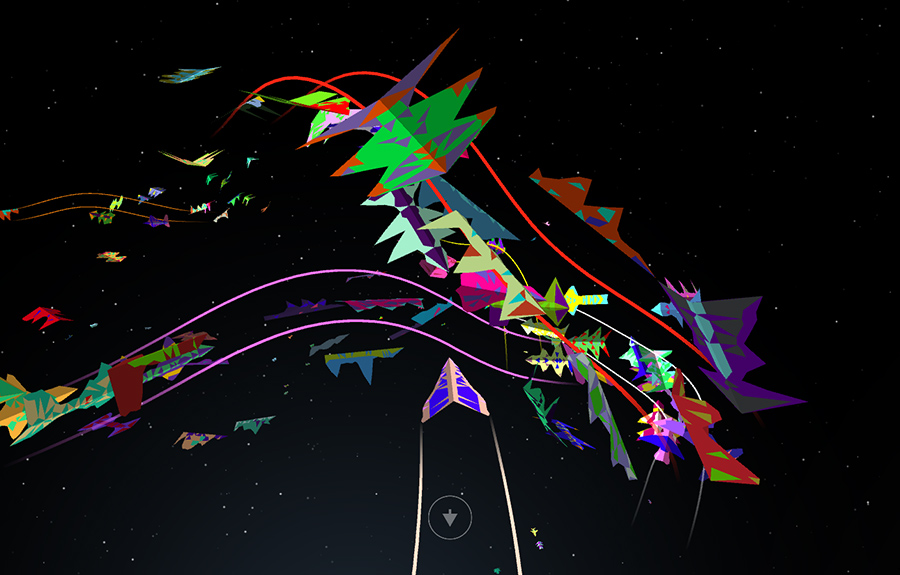

The soul and grace in Universal Everything’s video installations are a rarity in digital art. But it’s in the studio’s interactive work that you get a real sense of commitment to a relationship with the viewer rather than just a demonstration of its own talents. The 1000 Hands project at the Science Museum, for example, gave visitors the chance to co-create works of art on display, drawing their own creature-like forms that then sprang into life as moving graphics. “Our ideas always start from the context,” explains Pyke. “When the context is right, we work with interactive. Interactivity works best when there is a collective achievement, something created by the public. It’s much more emotive. Individual interaction can be interesting at an event but it’s a lot more fleeting.”

The potential of collective participation will be put into practice at an upcoming 27-screen installation at the Barbican, where the studio’s interactive work will be left entirely in the hands of the public. The only way it’ll work, explains Pyke, is if the installation manages to entice people. If no-one joins in, there won’t be any art. “I quite like that it’s as much of a surprise to us as the audience. We have no idea what it will become. It’s totally up to the power of the code and the minds of the public,” he says. “It’s really important that the interaction is really intuitive. It’s great if people walk into a room and the room wakes up and responds to them. If it needs instruction, it’s less successful.”

Alongside this participatory work, Pyke recognises that some people don’t want to experience such strong levels of engagement, while others don’t wish to work so hard to view art. Sometimes the experience works better at an individual level. The studio recently experimented with a particularly private experience by looking at the ownership of digital art – a concept that is growing increasingly pertinent if art is to ever exist in a world of BitTorrent piracy and Facebook sharing. Hosted at the Hospital Club in central London, in conjunction with online art platform Sedition, the exhibition featured a series of limited-edition video works that could not be copied. Once in the hands of its buyer, a piece could no longer be seen by anyone else. “We’re surrounded by so much general noise that passive video is something we’ll always be focused on,” says Pyke. “One day, we want to make a piece that only exists for an hour and then keeps writing over itself, changing and changing. So once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

It’s not just formats that Universal Everything is experimenting with. Pyke is equally interested in the application of science. “I’ve always been very curious and we’re always looking out for the next material to be inventive with. I follow science a lot,” he explains. “Developments at the forefront of science have very similar parallels to the world of art and design technology. They’re both nudging human evolution and knowledge forwards.”

This interest has led Pyke to explore material innovation, particularly physical forms – potentially a new direction away from screens for the studio. “We’ve been looking at using 3D printing and technology so pieces can take on a life of their own. After 10 years of making something untouchable that only exists behind a sheet of glass, it would be nice to get back to texture.” The transition to from digital design to physical is not without its challenges, however. “We actually tried to make a sculpture of a walking man, but ironically, because we made him an impossible form, it was impossible for him to exist outside of the screen.”

http://www.universaleverything.com/