Reframing Death

The narrative around death is no longer being avoided. To start exploring this broad and complex issue, we’ve asked a few of our contributors to offer their thoughts.

Over the past few weeks, discussions in our contributors forum have turned to death, but not in the usual depressing way. Think eco burials, urban mortuary infrastructure, and the rise of death cafés. Podcasts on grief are also gaining traction, and it’s clear that the topic is moving beyond a niche conversation.

There are cultural, political, environmental, even commercial angles to explore as brands start to realise the part they can play in shaping how we approach the end of life. What’s striking is how varied these conversations are depending on the lens through which they’re viewed.

But the overarching consensus is clear: the narrative around death is changing. What was once avoided or sidestepped is now being recognised as something that needs to be discussed more openly. To start exploring this broad and complex issue, we’ve asked a few of our contributors to offer their thoughts below, as well as a designer and a trend analyst who are also working in this space.

Featuring:

- Luisa Ferreira, a freelance cultural trends researcher and strategist from Brazil, working with agencies and clients across diverse markets. She originally planted this seed in the forum.

- Joe Muggs, a journalist and copywriter interested in the ways we frame subculture and represent cultural movements over time.

- Stefanie Schillmöller, a trend analyst and innovation strategist. In 2019, she founded Good Grief, a platform that reimagines death, grief and remembrance for the modern age.

- Anker Bak, a furniture designer based in Copenhagen, recently hosted an exhibition called “The Furniture We Need”, addressing “taboo” topics of ageing and death, and whose designs more generally are inspired by people in need of dignified and practical solutions.

How have attitudes towards death and grief changed in recent years?

LF: I believe this is something constantly evolving, perhaps because it remains a difficult topic to think about or discuss. With Covid-19, we were forced to confront death, our own mortality and the realisation that it is a natural, although challenging, part of life. For those who faced death or lost loved ones, it was also a time to rethink everything we had always assumed was far off in the future.

One significant shift, I would say, is the growing acknowledgment of mortality. From that awareness comes the question of how to navigate this reality and approach the topic in a less heavy and more constructive way. This includes fostering open conversations through podcasts, books and other platforms.

There has also been innovation in how we handle death practically, particularly around funerals and burial ceremonies. These include more sustainable options, such as eco-friendly funerals, green burials and even the innovative use of body materials. Additionally, there is a trend toward more personalised funerals and companies offering services to help families navigate the entire process, from the ceremonies themselves to providing support during grief.

JM: I think like so much in our global society, attitudes have exploded into myriad different iterations as we’re ever more able to access information from other eras and parts of the world. The full range from hyper-spiritual woo-woo to coldly pragmatic (and indeed combinations thereof) is all out there in the mix. But discussion has been turbocharged by the various levels of rage, denial and conspiracy that came with the Covid-19 pandemic, and extremely politicised (often deliberately radicalising) exposure of the developed west to violent death in conflicts whether in Ukraine, Palestine, Sudan or Haiti…

Add to that the still broadly unaddressed crisis of ageing populations (more advanced in, say, Japan or Korea, but rapidly hitting Europe and China), questions of guns and healthcare in the US, the debate on assisted dying, semaglutide and the next generation of drugs following it raising very real possibilities of life prolongation, and we’ve got a rich gumbo of viewpoints to say the least.

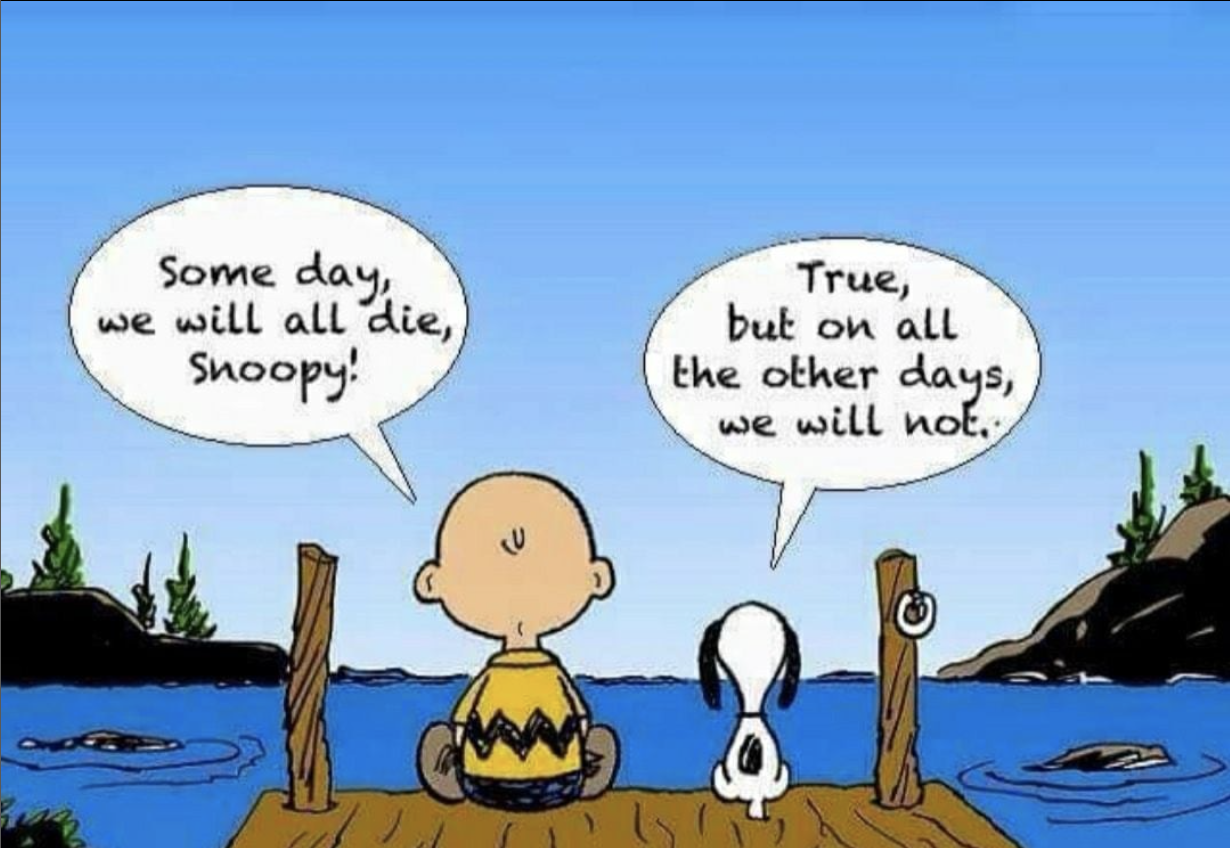

AB: What fascinates me is that, in our super busy lives, there is one thing we can be certain of: one day, we will die. Yet, people schedule everything in their lives down to the last detail – where to go on holiday, what to do every weekend – but when it comes to death, they want to avoid it.

In my view, this avoidance of death ties into our reluctance to accept ageing. We live in a world where social media and the fear of missing out are rampant, and people undergo all sorts of unnatural surgeries to fight the passage of time. This shows me that we’re unwilling to grow old, and if we can’t accept growing older, then it’s even harder to accept that we will die one day.

What’s important for me is to focus on how we age, not just what we age into. The first step is accepting that we grow older and learning to do so with pride. How can we respect older people more? In Japan, for example, there is much more respect for the elderly than in Europe. It’s not about making ageing “cool” or “fashionable” because those aren’t quite the right words, but how can we make it something to be proud of? We’re not forever young, but what we can do is learn to age with pride and live a life where we embrace the natural course of life, from birth to death.

SS: Western societies have begun to break the silence around death and grief. The Covid-19 pandemic acted as a collective wake-up call, forcing people to confront mortality on a global scale. Platforms like TikTok, through such hashtags like #GriefTok and #DeadDogTikTok, as well as various online communities elsewhere, have made death and grief more visible, talked about and communal, reshaping it as something to share rather than suppress.

Younger generations in particular view grief as a natural, even empowering human experience, rather than something that is shameful or isolating. This is fueled in part by a greater openness to conversations about mental health that normalise discussions of loss as an integral part of overall wellbeing.

Death positivity movements are amplifying this momentum, encouraging open conversations, challenging taboos around end-of-life planning, and shifting the perspective towards embracing impermanence as a core part of life. Recognising our mortality can deepen our appreciation of the present and inspire more intentional decisions that align with what truly matters.

Why should brands care about reframing the narrative around death?

JM: Well, none of those fraught topics I mentioned are going away! Brands are part of society, so it behooves them to contribute to better discourse where and when they can. Of course it depends on the brand and what they are selling, but even products that seem frivolous can address their parts in providing comfort to the grieving or being part of relationships between the living and the dead.

Personally, I feel like it would be better if more culture – which of course includes adverts and the like – treated these relationships to the dead as part of everyday life, without sentimental music or grandiose statements. When it comes to bigger issues, as with how we deal with the fact that the ageing population means that there are more of us as a society “looking death in the face”, that’s an altogether more complex question, and as with any complex and heavyweight issue really comes down to the personality and mission of the brand: is that brand mature enough and confident enough in itself to speak on the topic?

SS: Death and grief touch everyone, making them universal experiences with immense emotional resonance. For brands, addressing these topics with sensitivity can build trust and foster meaningful connections. Organizations that reframe death not as an end but as a part of life can lead the way in destigmatizing conversations that many consumers are already having.

To avoid opportunism, authenticity is key: partner with experts, prioritize education over sales and align efforts with genuine support systems, like grief counseling or awareness campaigns. Efforts should feel human and thoughtful, not exploitative or overly commercial. Brands like Recompose or Loop Biotech (offering eco-friendly burial alternatives) exemplify how to integrate innovation, purpose and respect into these discussions.

LF: I think it’s more about reflection and driving change. As widespread perspectives on this subject evolve, brands should also reflect these changes. There is a meaningful opportunity for brands to participate in the conversation and provide support during such sensitive moments.

AB: I think we need to rethink how we design healthcare products for the elderly. These products should not only be functional, but should give people a sense of pride when they use them. They should feel dignified, not ashamed, as they age. Small changes in design can help shift this narrative, encouraging people to talk more openly about ageing and death.

I’m currently working with two brands where we’re reframing Scandinavian design, which has largely remained unchanged for centuries. My goal is to create a deeper connection with products like coffins, which I prefer to think of as furniture. Although a coffin may never enter a home, it should still fit within the aesthetic and materials of the space. We spend so much time in our homes, so products related to death should resonate with the environment we know. This connection through form and material makes the experience less about the product’s appearance or colour and more about its integration into our lives.

When working with brands, especially in the coffin and healthcare industries, it’s not just about money. My focus is on delivering a meaningful experience. A future step for me is exploring how we can tell more stories about death – stories that help demystify it. People often avoid the subject because they are unfamiliar with it, and this makes it feel unclear or uncomfortable. My aim is to make this area more approachable, allowing people to find interest in, and perhaps even beauty in, the stories surrounding death.

What possibilities do you see for innovation in how we think about, talk about or experience death?

SS: Innovation in this space has immense potential - from technology (many processes are not yet digitalised) to new rituals. Virtual reality could allow people to preserve and revisit memories of loved ones in immersive ways. Sustainable deathcare, like aquamation or biodegradable urns, is redefining how we connect with the earth even after life. There’s also room for creative mourning spaces, such as grief-focused digital communities or experiential art installations that foster collective healing. Innovations in end-of-life planning can alleviate the overwhelming financial and logistical challenges that often accompany death. At its core, innovation should aim to normalise death as part of life, breaking down fears and barriers. By integrating creativity, technology and emotional intelligence, we can transform grief from something to avoid into an opportunity for connection, reflection and growth.

AB: I started working in this field six years ago. But more designers need to join me. Because things haven't changed much in many years. We need more innovation and new perspectives. How can design change in the same direction as the rest of society, with all the dignity, beauty and spirituality around it? I would really like to have the answers! If we have a more holistic society, then we need to engage more with that part of life where death is also. Death is an important part of life, and we shouldn’t ever forget it.

LF: I believe there’s significant room to talk more openly about death as a collective subject and shared experience. Innovations that help people navigate this situation in groups, provide listening support or foster connection could make a big difference. We already have examples like AI tools for grief support or grief-focused coffee spaces, but there’s a need for more solutions that encourage speaking, listening and sharing as ways to cope. I also believe that companies providing services related to death, from handling bureaucracy to offering grief support, will continue to grow. There is also an increasing demand for more sustainable and personalised ceremonies, as well as innovative ways to preserve the memories of loved ones, especially considering the vast amount of online material we now accumulate. These are some innovations that come to mind at the moment.

JM: Two things that spring to mind are AI and psychedelics therapy. People are increasingly finding that conversations with LLMs allow conversations about heightening topics to be conducted in a cooler tone – and there is significant literature that shows the principles of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy are surprisingly easily automated. The progress of experiments with drugs like ketamine, psilocybin and MDMA in therapy for trauma – and thus changing attitudes to death – is slow but promising. Of course both of these carry big risks, and must be managed and approached carefully, which is hard in two fields riddled with hype.

Further Reading/Listening

I’m Fine Podcast by Jean Campbell

“I’m Fine is a podcast that aims to foster conversations around the myriad forms of suffering that so many are navigating, often in silence. Redefining the narrative of pain in our lives, discovering mind-body methods for moving beyond pain and accessing possibility, positivity and productivity to find our power.”

The Race to Optimise Grief by Mihika Agarwal

“While mimicking conversational style is just one of the many uses of the popular generative chatbot ChatGPT, there’s a niche yet growing slate of platforms that use deep learning and large language models to re-create the essence of the deceased. Hailed as ‘grief tech,’ a crop of California-based startups like Replika, HereAfter AI, StoryFile, and Seance AI are offering users a range of services to cope with the loss of a loved one — interactive video conversations with the dead, ‘companions’ or virtual avatars that you can text day or night, and audio legacies for posterity.”

Dying Livingly by Staci Bu Shea

“Part studious, part visceral, Dying Livingly is a collection of short essays written in the first few years of the author’s holistic deathcare research and practice. With a focus on the truth of impermanence and the material cultures of death and dying, the writing reaches toward a future of compassionate, community-centred deathcare.”

Based at Columbia University GSAPP, the DeathLab is a trans-disciplinary research and design space focused on reconceiving how we live with death in big cities. DeathLAB is working on an alternative to traditional burial methods, and designs new public spaces of remembrance “intertwined with everyday life”.

| SEED | #8287 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 21.01.25 |

| PLANTED BY | PROTEIN |

| CONTRIBUTORS | LUISA FERREIRA, JOE MUGGS, STEFANIE SCHILLMÖLLER, ANKER BAK |

Discussion