For the modernist designers, such as Eames and van der Rohe, form always followed function. But for Oki Sato, founder of Japanese design studio Nendo, form also follows narrative

For the modernist designers, such as Eames and van der Rohe, form always followed function. But for Oki Sato, founder of Japanese design studio Nendo, form also follows narrative

‘It’s about what kind of story you can find behind the object,’ says Oki. ‘Whether it’s a chair or a computer mouse, it’s all the same to me.’

These stories enable Nendo to fulfill its design philosophy: to transform people’s interaction with every day objects (an approach described on the studio’s website as ‘giving people a small “!” moment’). It does this by creating a form that's minimal but full of character. ‘I like my designs very simple,’ says Oki. ‘But I don’t want to make them cold. It needs a pinch of humour or friendliness.’

Nendo means ‘clay’, specifically a malleable type, such as children’s Play-doh. ‘It changes form, shape and colour,’ says Oki. The name is fitting for a studio that needs to evolve and change to produce design solutions for the wide variety clients that knock on its doors. Founded in 2002, after Oki visited his first Salone del Mobile design fair in Milan, it has since quietly become one of the most prolific contemporary design studios.

People are interested in small stories now because of the media. Before it was newspapers and television. Now it’s more about Twittering small moments. It’s similar to the way I think about design.

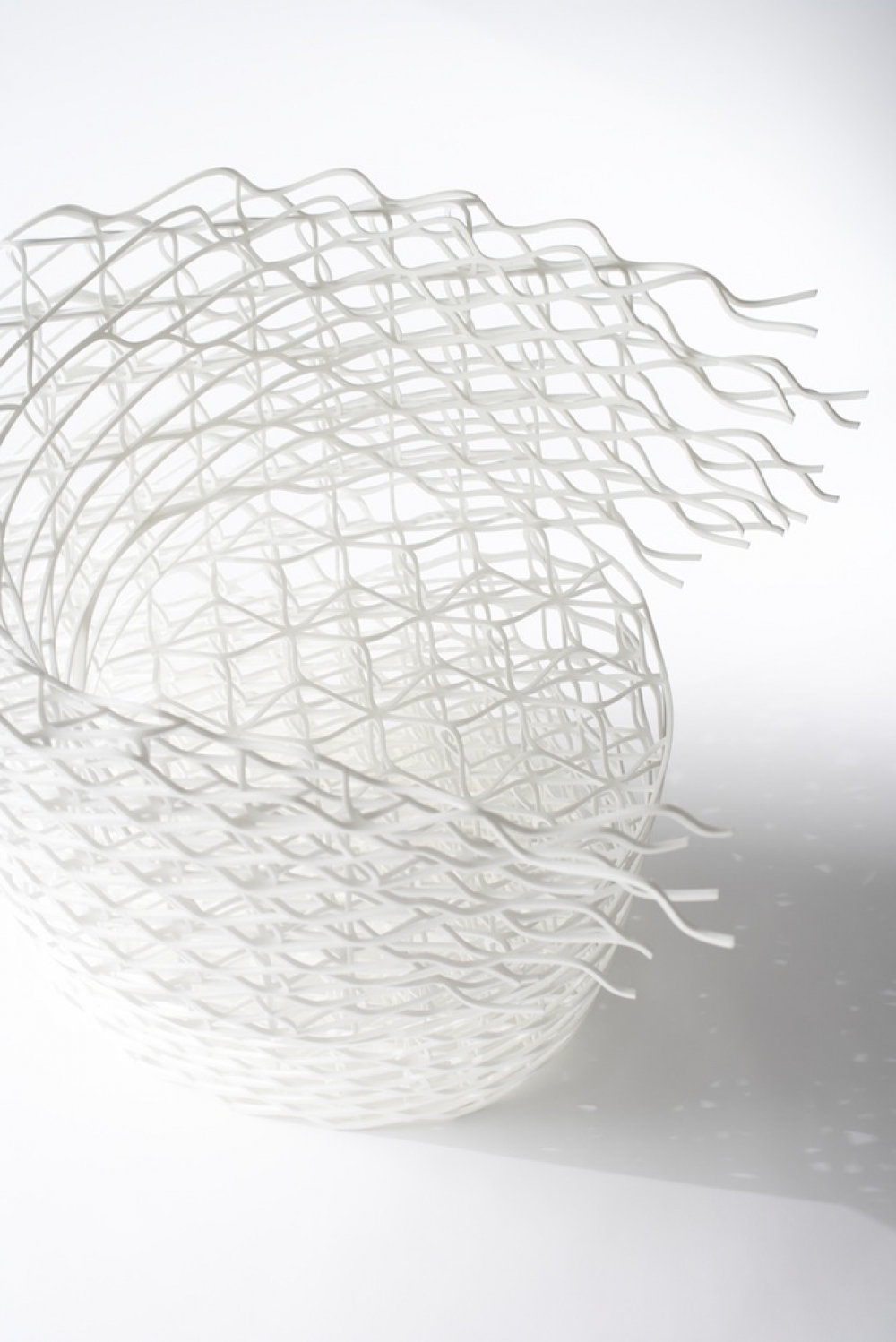

Recent work includes a case and glass holder for the brand Ruinart, which lets people have a place to rest their glass when outside. Oki has also turned his hand to interior design, where he has created retail spaces that help to enhance the way simple merchandise and products are displayed. For the Issey Miyake’s 24 store, built for department store concessions in Japan, Nendo created a cluster of narrow steel rods for folded clothing to sit on. It designed an interior for a Puma show room in Japan, called the Puma House Tokyo, where sneakers are placed on timber stairs that spiral around large concrete columns.

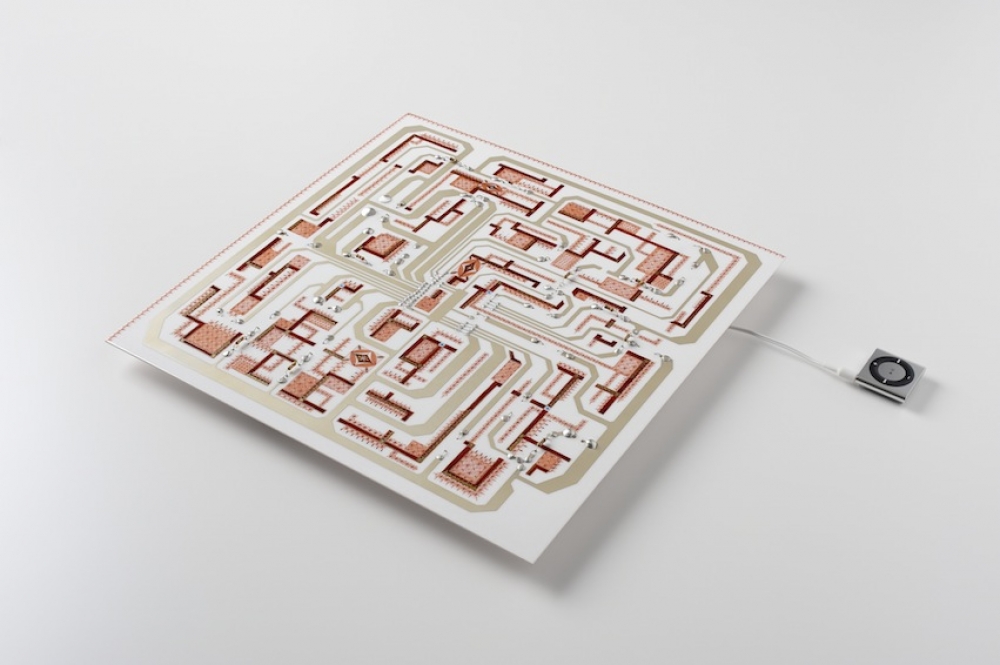

Nendo has also turned its hand to furniture design, with collections that have appeared in renowned galleries around the world, much to the praise of the design press (the Thin Black Lines exhibition at the Philip de Pury gallery, for instance, was a highlight of last year’s London Design Festival). Most recently, Oki worked with British furniture brand Established & Sons for this year’s London Design Festival, where it created an installation called ‘My London’ that represented the city and its population. Oki created thousands of different small, Post-It-sized maps, and attached them to the walls of the brand’s showroom in East London. The result was a giant white cloud of paper - a collective of all the small moments experiences by the city’s population. ‘London doesn’t have a certain colour or face,’ explains Oki. ‘It’s different to every person. It was all about the small memories of different people.’

Next year Nendo will be ten years old. To celebrate, Oki is planning a series of exhibitions that will travel around the world. But despite having been in design for almost a decade, Oki’s approach, and his interest in the narratives behind design, hasn’t dated. In fact, it’s only become more pertinent. ‘People are more interested in small stories now,’ says Oki. ‘It’s maybe because of the media. Before it was newspapers and television. Now it’s more about Twittering small moments. It’s similar to the way I think about design.’

Discussion