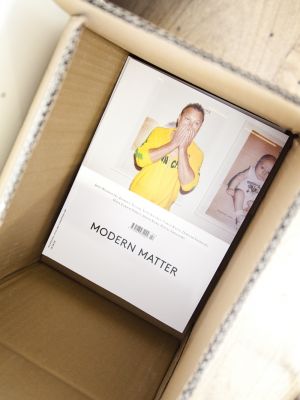

Modern Matter

Olu Micheael Odukoya talks Modern Matter, a new magazine that explores the burgeoning digital zeitgeist

‘When you think about technology magazines, you normally think of Wired. The content is similar, but we do it differently.’ Olu Michael Odukoya is tired of today’s independent culture magazines. ‘Back in the 80s – when you had magazines like The Face – music and art was just so fresh,’ he says. ‘But I couldn’t work in those mediums anymore. The bands just aren’t original today, you know?’

That’s not to say that Olu, founder of Kilimanjaro magazine (and a trained optician), is bored of all modern culture. Far from it. It’s just that his curiosity doesn’t lie with over-celebrated fashion darlings or trust-funded photographers like it does for so many of today’s art bookshop titles. Rather, Olu is interested in what’s really current and new: digital culture.

So earlier this year he started his second magazine, Modern Matter, in which he explores this burgeoning digital zeitgeist. But don’t expect Facebook IPOs and the latest Apple products. ‘When you think about technology magazines, you normally think of Wired,’ says Olu. ‘The content is similar, but we do it differently.’

This difference – and what Modern Matter manages to do extremely well – is to explore the human and cultural significance of digital. So while it contains stories of the usual Web 2.0 suspects – Tumblr, Youtube, Twitter – the writing delves much deeper, often with an anthropological perspective, and features the sort of analysis found in a small-run, indie arts mag. Plus there’s an element of menswear throughout. It’s Wired meets Fantastic Man. Or as Olu puts it, ‘technology content presented in a cultural magazine.’Take the profile with David Karp, the 40 million dollar man behind visual-blogging platform Tumblr. There’s the story of his rise to fame and the success of Tumblr, of course. But business aside, it also investigates the behavioural significance of the platform, such as Dawkins’ theory of how ideas spread virally across the Web, and the uncomfortable consequences of this, like the spread of messages of eating disorders and self-harming. It also forgoes shooting Karp as a man-in-a-suit with a look-at-my-success style that’s typical in most tech mags.

Well, actually, Karp is in a suit. But it’s a cool, casual suit – Prada complete with an Adam Kimmel shirt – worn during a stroll through New York (the sort of attire you’d expect him to wear to his next VC meet). It shows success, but an easy-going success – the type associated with many of today’s young web entrepreneurs that seem driven by the global possibilities of the internet rather than just making a shit-ton of cash.

There’s also a brief glimpse of Jack Dorsey, micro-blogging posterboy and co-founder of Twitter, caught on camera during a moment at the DLD conference in Munich, Germany. ‘When he’s on the cover of Time he looks unnatural,’ says Olu, ‘but when we showed him in Modern Matter – it’s still serious – but it’s more original to what tech is about. And that’s what makes it more like art: we captured him like the superstar that he is.’

Modern Matter also uncovers some of the hidden behaviours of the Web, instigated by the people who use these platforms to indulge and promote their personal interests. An example is Aaron Eastham, who has a channel on Youtube featuring videos of his smoking. Tune in and you can see the Eminem-like figure puffing away on a Marlboro Red on webcam for his followers (now 600 strong). Reading the comments underneath the videos (‘You are my HERO. Keep smoking hard, keep smoking hard’), it’s not easy to decipher if Eastham’s online antics are a curious consequence of anti-smoking laws or stimulation for people with a fetish for a young, shirtless lad holding a small tube to his lips.

Eastham is the only moment of bizarre though. The majority of Modern Matter reads like a high-culture mag. In fact, the editorial isn't strictly about digital, which might seem contradictory to the direction of the magazine, but is perhaps necessary in order to underline the broader cultural theme. There’s interviews with architects, actors and art curators – the criteria always being that the subjects are men that make legitimate contributions to culture and the arts (or as the spine says: ‘A Journal For Men That Matter’). And Modern Matter isn’t afraid to get serious about it: copy is dense and cerebral. One feature, for example, is a full transcript of a lecture given by technology author Michael Stutz, with an accompanying set of photos from the unnamed event it was given at.

All this content – the start-up superstars, the sub-subcultural instigators, the academics – is wrapped up in Modern Matter’s deliberately haphazard design, which chops and changes throughout. While some graphic designers might squirm at the idea, there is method to this madness: each piece is presented in a visual identity that’s appropriate to that particular subject matter (academia looks like a refined journal, while subculture pieces have an appropriately unfinished edge). The clunky style is reminiscent of the unfriendly design seen in many of today’s modern websites.

There’s also an element of evolution to Modern Matter. Just two issues of the magazine have been published, but both look significantly different, with the main change being that the first issue was simply called ‘Matter’. ‘Every issue is edited in that way’, says Olu. ‘We had problems with the name 'Matter', so we thought, ‘what about Modern Matter?’ And that’s what we went for. So we changed the style and emotion.’ While this seems like another rash decision, there’s something about it that reflects the beta-testing nature of digital, with its just-put-it-out-there-and-see means of launching new design. Or as Olu puts it, it's another way of maintaining the ‘rawness.’

Photography: Teddy">http://teddyfitzhugh.tumblr.com/">Teddy Fitzhughhttp://www.amodernmatter.com