Medieval Nostalgia

How the surge in Medieval-inspired culture and branding reflects a longing for simpler times – featuring underconsumption core and Chappell ‘Roan of Arc’.

Initially inspired by typography, and mostly from YouTube thumbnails, the theme of Medieval nostalgia has been on my mind. In some ways, I couldn’t help it. The fascination with an ancient world populated with heroes and myths was seemingly everywhere I looked.

It was there when I started listening to the Goes Without Saying podcast and subscribed to the hosts’ YouTube channel, ‘Sephy and Wing’, noticing that a lot of the fonts had a Medieval, gothic look. Most notably, perhaps, it was there in the poster for the film Saltburn, which used a custom font called Salium, from FG Studios, inspired by writing styles from manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Elsewhere, Chappell Roan truly committed to Medieval style at the MTV VMAs in February, with outfits ranging from a suit of armour and flaming crossbow on stage to a hooded chainmail dress when accepting the Best New Artist award.

Medieval fonts appear particularly anachronistic in the digital age – conveying a kind of detail-driven, handmade relationship to the written word that has been antiquated since the invention of the printing press. I was intrigued by what made Medieval fonts and styles the go-to choice for everything from a podcast targeting Gen Z women to a blockbuster cinematic release.

Bardcore is a musical microgenre I became aware of after hearing a cover of Yeah! by Usher. Featuring covers of pop, R&B and rap songs using Medieval instrumentation, bardcore emerged around 2020 with accounts like Beedle the Bardcore and Hildegard von Blingin leading the genre. Most bardcore is instrumental, and the tunes are always familiar. I think hearing a good Medieval style cover of a modern song, from Africa by Toto to No Scrubs, is such a joyful experience because it connects you to a timeless sense of how music and its emotional associations can be conveyed, regardless of the instruments and technology available at that point in history. As one commenter puts it under the ‘Yeah!’ but it’s Medieval’ Youtube video:

The brand Teenage Engineering has explored what it means to produce Medieval music with modern technology. Its synthesiser EP-1320 Medieval is, apparently, ‘the world’s first Medieval electronic instrument’ and an ‘instrumentalis electronicum’, featuring a library of medieval sounds from hurdy gurdys to Gregorian chants. I love how much the art direction commits to the bit, encompassing the marginalia style illustrations of medieval figures playing with EP-1320, live action videos depicting its ritualistic treatment and Gothic style fonts on the synthesiser itself. Accompanying merchandise, including t-shirts, keychains and quilted bags, similarly aims to expand the brand world, bringing these esoteric references IRL.

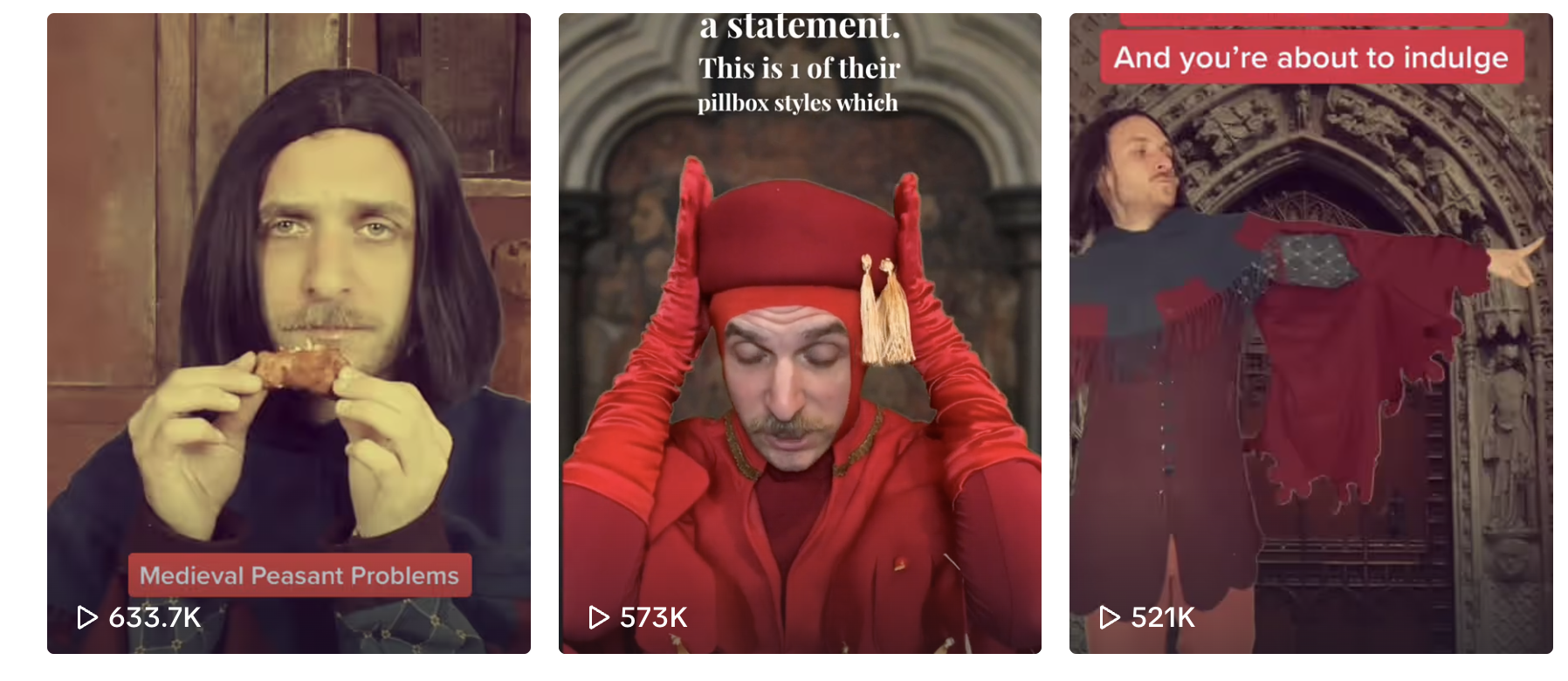

Another artefact of Medieval-inspired media that I am obsessing over is the ‘Every Podcast in the 1200s’ series of sketches by Boys Gone Wild. The original video went viral, with 3.8m views on TikTok, and there are now five parts to the series. The ‘boys’ satirise the male podcast genre, repurposing tropes from casual misogyny to performative vulnerability with archaic references, with lines like ‘if she don’t weave, brod’s gotta leave’, and ‘It’s 1242, we need to start changing narratives around gout’. As with the bardcore genre, the series derives its humour from the contrast to contemporary culture, in its reworking of our favourite media formats for the Middle Ages.

In the food and drink space, Medieval eating habits are also gaining interest. In the ‘girl dinner’ trend from 2023, the original creator Olivia Maher actually offered an alternative name, saying in the viral TikTok video ‘I call it girl dinner, or Medieval peasant’. The video is also tagged with #medievaltiktok, a hashtag with over 560,000 posts. Whilst it was the ‘girl dinner’ name that went viral, the ‘Medieval peasant’ alternative is intriguing for its reference to the imagined simplicity of peasant life, where a hunk of bread, some cubes of cheese and a handful of grapes could be a satisfying dinner.

The ‘perpetual stew’ viral moment from @depthsofwikipedia creator Annie Rauwerda also captured a fascination with a more communal, less wasteful, way of eating that was common in Medieval inns. The stew can remain cooking, and therefore consumed, for exceedingly long amounts of time, as the constant boiling means that bacteria cannot form. Rauwerda’s perpetual stew lasted 60 days and involved several meet-ups in Brooklyn, New York, where participants could add a chosen (non-meat) ingredient to the stew and sample a bowl themselves. There was a giddiness you could sense in the TikTok documentation of the stew meetups, at the collective effervescence of participating in such a wholesome (yet chronically online) collective activity.

In these signals of the resonance of Medieval times in pop culture, we are shedding light on the overwhelming nature of our own societies – by producing Medieval versions of contemporary culture – and reflecting a desire for greater simplicity – by romanticising the frugal lives of the past. This interest in ‘going back’ to a simpler time is clear across culture, from ‘tradwife’ content to paleo diets. Of course, we can see it in our politics as well, with far right movements (Trump is as an obvious example) capitalising on a wish to return to an imagined ‘golden age’. The cost of living crisis also makes frugality a necessity for many, making ‘Medieval peasant’ dinners a similar aestheticisation of thriftiness as ‘underconsumption core’ or ‘dupe’ discourse.

However, from doing more research into the Middle Ages, I realised how weird and wonderful a time it actually was. Humorous contrasts or parallels between contemporary life and peasant-like simplicity is one factor contributing to the renewed interest in this period of time. What’s more, exploring aspects of performance and flamboyant expression contained within Medieval history provides another point for understanding deeper resonances with the present day.

I was struck by how explicitly pop star Chappell Roan referenced Medieval imagery this year around the promotion of her single ‘Good Luck Babe’ and at the VMAs in September. The Medieval styling can be tied to the baroque pop elements of ‘Good Luck Babe’, as well as a vehicle for elaborate drag that Chappell Roan has become known for. Much commentary has drawn a connection to Chappell Roan’s armour-like styling and her statements asserting her boundaries and need for privacy on social media. However, she was already referencing Medieval times in the cover of Good Luck Babe back in April, with a Tudor style headdress and fairytale curse appropriate (à la Penelope) prosthetic pig nose.

The ‘weirdness’ of Medieval styles has even been codified into TikTok fashion ‘cores’, like ‘Medieval Weird Core’ and ‘Weirdeval’. These build on historically inspired aesthetics like ‘regency core’ and ‘coquette’, with a dark ages twist.

One online creator embracing the potential for queerness and drag via the Middle Ages is @greedypeasant, who describes his account as a ‘Queer Medieval Fever Dream 🏰💅’. The Greedy Peasant character is obsessed with tassels, pageants, astrology and cemeteries, with videos featuring tasselled, feathered, sequinned and otherwise elaborately decorated outfits and and costumes for pageant participants. His enthusiasm for pageants and saint days as opportunities for dress-up and hedonism parallel the ways that ‘balls’ acted as vehicles for more explicitly queer expression in 80s and 90s New York. The current ‘renaissance’ of Renaissance Faires can be similarly seen as an outlet of expression that can be used to explore queerness with an antiquated twist. Greedy Peasant’s videos capture the genuine ways that people in Medieval Europe created outlets for celebration and pleasure-seeking, within the context of an otherwise hierarchical, heavily Christian society.

In visiting the Medieval Women: In Their Own Words exhibition that has recently opened at the British Library in London, it exposed how women specifically accessed power within and/or subverted existing structures in the Middle Ages, to find their own modes of expression. I was particularly interested in the sections that highlighted how women used their spiritual lives and religious institutions as a source of power. The classic example, included in the exhibition, is Joan of Arc, a figure so iconic in our imagination that Chappell Roan wearing a suit of armour at the VMAs prompted many ‘ROAN OF ARC!!!’ comments online. A woman having the bravery to speak out while carrying the risk of ostracisation from society can feel particularly resonant in an age of discourse around public figures getting ‘cancelled’ or ‘woman-ed’.

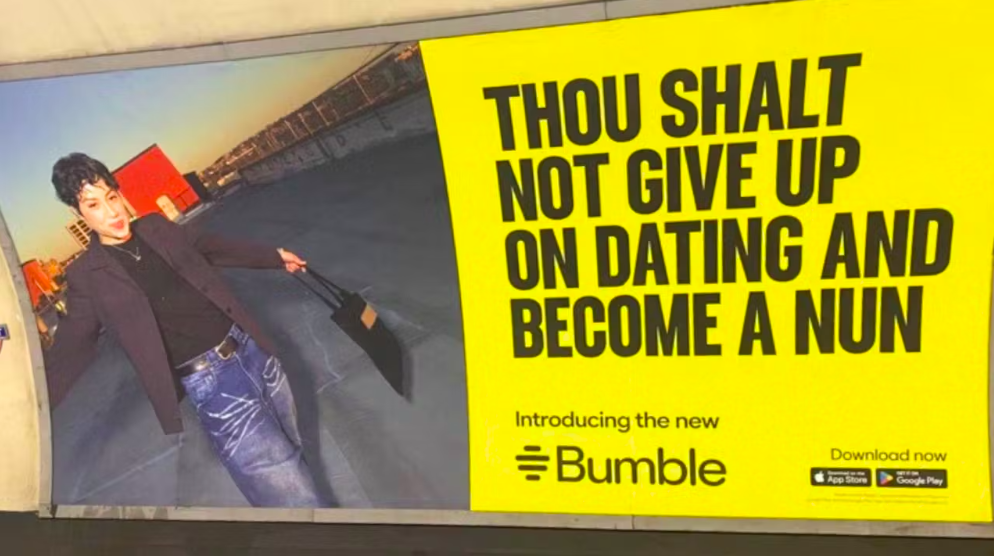

The exhibition goes beyond Joan though, looking at other heretical female figures alongside women involved in traditional religious structures like nunneries. Becoming a nun allowed some Medieval women to escape the expectations of servitude through marriage and domestic life to access opportunities for education and creativity, albeit within the restricted life of nunneries. The depiction of these means of empowerment through chastity made the recent controversy around the Bumble campaign – claiming, ‘You know full well a vow of celibacy is not the answer’, with a video advert depicting a nun being tempted out of the convent with the Bumble app open on a phone – interesting to consider. While the existence of nuns isn’t limited to the Middle Ages, the backlash suggests a parallel between how Medieval women sought to subvert the limitations of patriarchal structures and the ways women today challenge similar constraints.

While this can be seen as an another expression of the idealisation of simplicity, and even restriction, the Medieval Women exhibition also showed the role of women in more ‘alternative’ spiritual practices that subverted restrictive structures. This included an interactive ‘Would you be suspected of witchcraft?’ quiz, as well as references to use of horoscopes and folk healing. This was a form of knowledge that women were seen to exercise power through, but was simultaneously feared and scapegoated for the harm these practices were believed to cause. With the contemporary resurgence of spiritual practices such as astrology and taro, we can see a contemporary fascination with practices offering alternative ways of meaning-making.

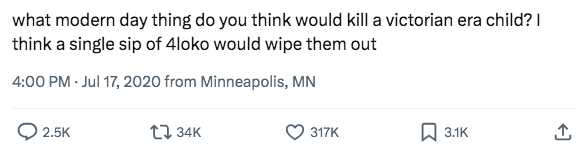

With all these examples of the resonance of diverse aspects of Medieval culture in 2024 in mind, this still leaves the question – why is there ‘nostalgia’ (or at least interest) for the Medieval period in particular? This isn’t the first time we have seen online content and discourse about bygone eras, from talking about your own personal ‘Roman Empire’ to the ‘this would kill a Victorian child’ meme. So what is making Medieval times an emergent subject in culture?

It’s important to clarify here that this ‘nostalgia’ is for Medieval Europe in particular, and not the broader world during the same time period. Even the construct of ‘Middle Ages’ or ‘Medieval’ is Eurocentric, referring to the period between the fall of the Roman Empire in Europe and the Renaissance. This European focus can also explain some of the popularity of this trend. Looking at notable microtrends over the last few years, from biker and ‘motto’ styles to Western wear, ‘cowgirl’ aesthetics, cottagecore and coquette, there is increasingly a reorientation towards aesthetics rooted in Western and/or European subcultures and time periods. Partly, this reflects a greater awareness (and therefore avoidance) of cultural appropriation – specifically of non-Western cultural styles and sometimes practices. ‘Medieval nostalgia’ can be seen as the latest iteration in renewed contemporary interest in historical Western aesthetics.

At the same time, the Middle Ages are perceived as a time period a degree removed from the entrenchment of perceived Western superiority and racism. Whilst the foundations for modern European imperialism and slavery were already being laid in the Middle Ages, from the Crusades to the beginnings of the Portuguese colonisation of the Atlantic islands in the 1420s, the Medieval period is not as aesthetically associated with these systems of oppression. This makes it appear unburdened enough by the violence of modernity to be a ‘lighter’ subject for cultural exploration. This may explain why medieval times are heavily associated with the fantasy genre, with tropes being employed in popular fantasy media like ACOTAR (A Court of Thorns and Roses) and Game of Thrones, because it is a time period distant enough to decontextualise and, as such, romanticise.

Additionally, while the Medieval period is often embraced for its distance from our contemporary lives, it also has deeper resonances with life in the 2020s. I have touched on several parallels already, from the romanticisation of peasant simplicity as a response to the cost-of-living crisis to the potential for queer interpretation of Medieval traditions of flamboyance and performance. A further factor to be reckoned with is the impact of the Bubonic plague across whole societies in the Middle Ages, which has some similarities to the catastrophic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Plagues in medieval times made people painfully aware of their vulnerabilities and changed social structures, as they do today. The absurdity of reckoning with our mortality in the midst of catastrophic social change, whilst living within rigid social structures invested in the status quo, remains poignant for us as present-day ‘peasants’.

Satirising and reinterpreting Medieval tropes and imagery for content will surely wane in popularity at some point. But the instrumentalisation of the past to make sense of our current place in space and time will continue in new weird and wonderful ways.

This is an edited extract from Jade Isaacs' Substack Anthropop, an anthropological perspective on culture and trends.

| SEED | #8281 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 10.12.24 |

| PLANTED BY | JADE ISAACS |