KP Kofler: Pret A Diner

The dark, dank tunnels underneath London’s Waterloo station are probably the last place you’d expect to eat fine cuisine.

The dark, dank tunnels underneath London’s Waterloo station are probably the last place you’d expect to eat fine cuisine. But last week they were the setting for a temporary event that combined the usually removed worlds of street art and fine dining, and placed both inside an equally unexpected space.

The event, The Minotaur, was a collaboration between street art curator Steve Lazaridis and KP Kofler, the founder of German temporary restaurant, Pret a Diner. The pair had set up the temporary dining and food event within the damp, underground caverns of the Old Vic tunnels as part of this year’s Frieze Art Fair. And the result was a a curious mix of the refined and unrefined.

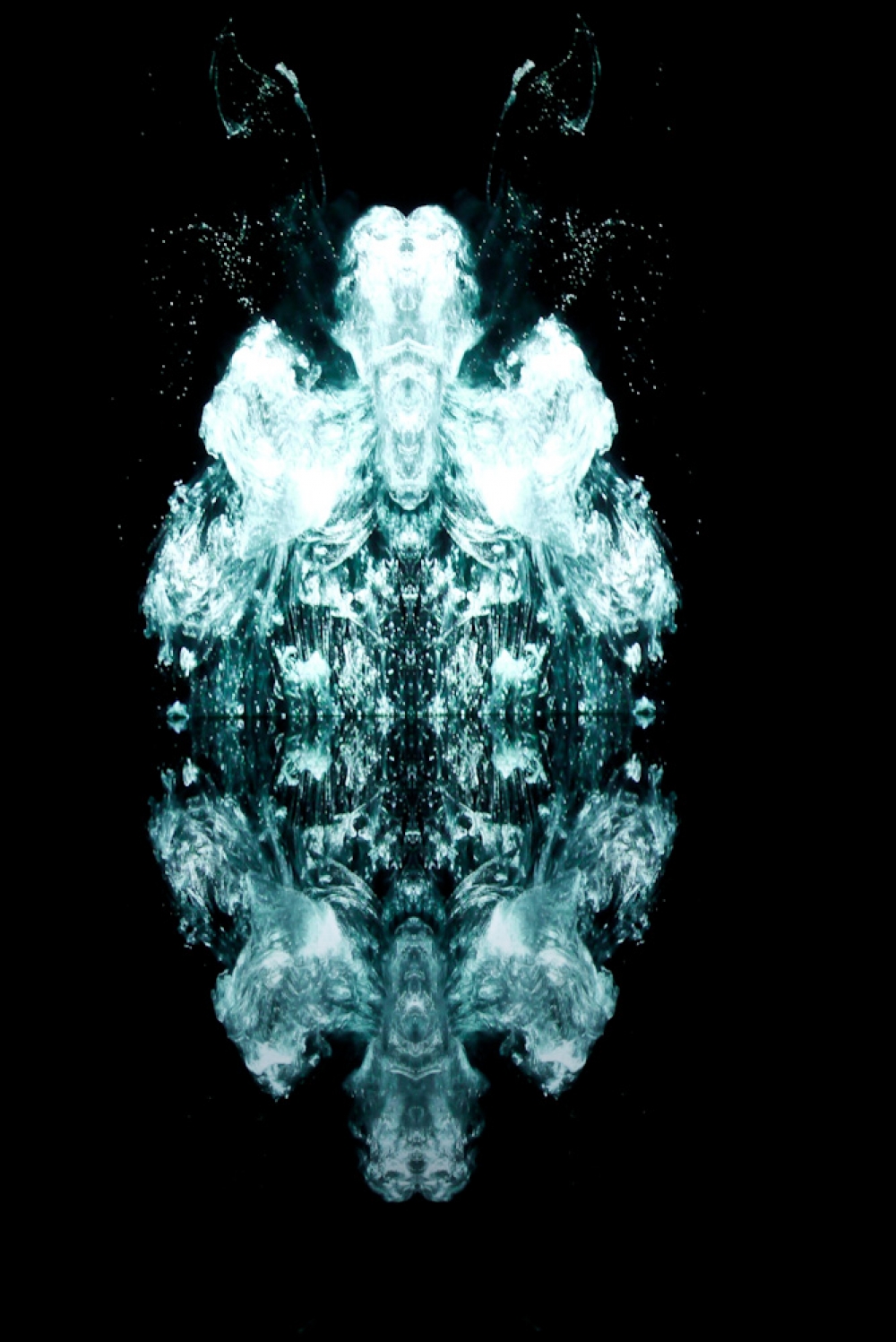

The complex of caverns that make up the underground architecture created a labyrinth of spaces, which were filled with a continuous soundtrack of creepy music and a faint smell of damp. Each contained a different work of art that the guests stumbled upon as they entered each area. In one room, the image of a creature made from plumes of smoke had been projected on to a giant screen, and was reflected back down into a dark, shallow pool of water below. Another featured a series of tribal figures, with giant masks that stood along a passageway, and looked like a group of hunters marching off to a kill. And towards the end of the trail, a curious monolith stood, pointing upwards to the roof above. On first glance this looked like an abstract sculpture. But on close inspection, the piece had been made from hundreds of dead rats, each crafted with realistic detail.

Normally if you go to a fine dining restaurant you see classic art on the walls and a formal atmosphere. But nowadays, people don’t want to be entertained in a way they are used to. All of these works had been curated by Lazaridis, who had turned to his roster of street artists, including Stanley Donwood, Doug Foster and ATMA, and asked each to produce work in response to his theme of Greek mythical beast, The Minotaur.

But the art was only half the story. The guests - had the more morbid installations not taken the edge off their appetites - were later ushered into a temporary restaurant area, which had been filled with vintage decorations and chandeliers fit for the coming banquet. Once seated, they tucked into a series of fine dishes, which had been made by an international group of renowned chefs. Nuno Mendes, formerly of El Bulli and now head chef at Viajante in London’s Bethnal Green, served a dish based on gathered and foraged ingredients. Others included Amador’s Juan Amador from Mannheim in Germany, and Matthias Schmidt of Villa Merton in Frankfurt. All of them had been gathered by Pret a Diner’s Kofler, and had been set a challenge to feed guests in the temporary kitchen.

The overall concept - matching refined food with an unrefined surrounding is certainly a juxtaposition. It’s not everyday you get to see art and eat a meal inside a tunnel, after all. So why do it? The reason, says Kofler, was to push people’s expectations of fine dining. ‘Normally if you go to a fine dining restaurant you see classic art on the walls and a formal atmosphere,’ says Kofler. ‘But nowadays, people don’t want to be entertained in a way they are used to.’

But the concept also highlights a more pressing issue for the restaurant industry: that refined dining as we know it doesn’t quite cut it anymore. Today - with supper clubs, molecular gastronomy, and culinary artists feeding us everything from coal to dirt - the rules have changed. The white table cloth restaurant is starting to look stale. And this is all to do with a change in mindset of the diner. ‘People don’t want to pay a lot of money for good food anymore,’ says Kofler. Instead, predicts Kofler, the future for fine dining might look a little more dirty.

http://www.pretadiner.com

Discussion