How To Assemble A Kick-Ass Collective

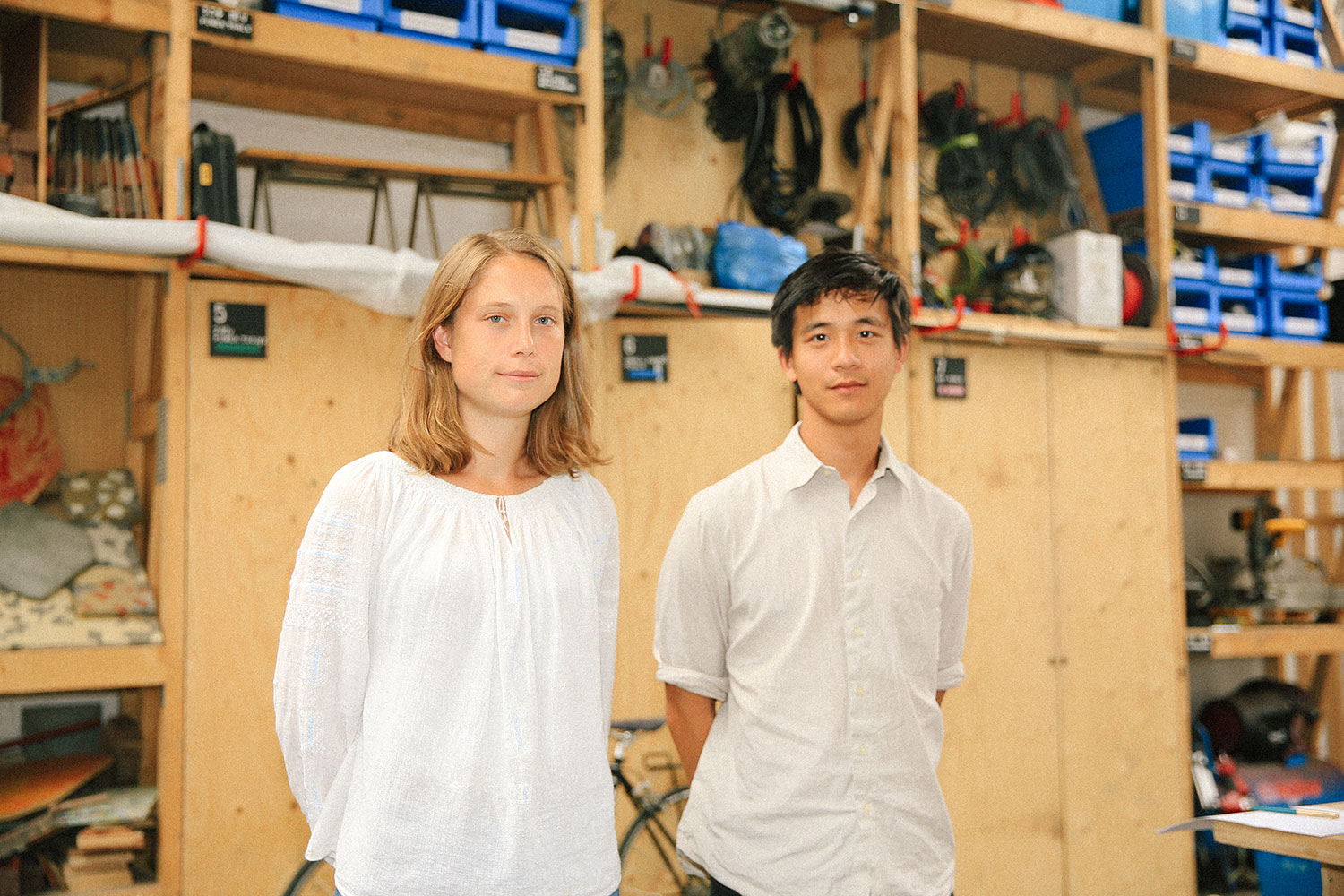

Meet the Turner Prize winners, architecture collective Assemble.

Ever since Assemble constructed a temporary cinema under a flyover in Hackney it's been praised by the design world for a community-driven approach to architecture. Now with the title of 2015 Turner Prize winners under their belt, it's about to wow the art world as well

The concrete no-man’s land that divides East London and the Olympic Village is not an attractive, fashionable, or even very accessible place for an architecture and design studio. But that makes it all the more fitting for the headquarters of Assemble, a young collective who have built their reputation on finding witty and resourceful answers to imperfect situations, often in landscapes just like this.

With their open, collaborative, project-by-project approach, Assemble have turned a lack of experience into their greatest asset, and given people a new degree of involvement in designing the spaces they will use. And now they are not only securing major commissions such as a new gallery for Goldsmiths University, but have also achieved suitably unusual recognition with a nomination for Britain’s top contemporary art award, the Turner Prize.

Assemble is composed of fourteen individuals, all still in their twenties, and incorporates members from very different backgrounds. It first came together in 2010 around a group of disillusioned architectural assistants who wanted to get out and build something. That turned out to be the Cineroleum, a makeshift cinema in the shell of a disused petrol station on Clerkenwell Road.

No one can fire anyone because we’re all friends Two of the founding members, Alice Edgerley and Matt Leung, explain how the collective was forged in this venture. “The project wasn’t an architecture project,” says Leung. “It was about running a bar, programming films and that kind of stuff.” In an all-hands-on-deck atmosphere, everyone merged into the fabric of the team.

Assemble’s early work continued with the theme of using inexpensive materials to conjure surprising designs in tricky urban spaces. Many were temporary, although beside their Stratford workspace they have a monument to this methodology in the form of the Yardhouse, a simple wooden-framed structure whose façade of mottled tiles has drawn the city’s selfie-brigade en masse to this unlikely grey landscape.

With their range of skills the team soon became dizzyingly versatile, and in the last five years have worked on performance venues, workshops and town squares, as well as more artistic projects such as the Brutalist Playground they installed at the Royal Institute of British Architects earlier this year.

Assemble has no hierarchy, but the chaos of joint decision-making is compensated for by emotional support and the quality of ideas. “It’s probably one thing that’s absent from most offices, the idea that everyone has an input,” says Edgerley. “It also means no one can fire anyone, because we’re all friends.”

Naturally, as the operation has grown, it has been a challenge for the group to maintain its spontaneous energy – especially as everyone has to make a living. “The thing that we’re trying to do now is find the way that we can all work in gainful employment in the same way that we started working together when we were doing it for fun,” explains Leung. “We don’t have loads of younger people to do all the work for us.”

Assemble’s answer to this problem is what it affectionately terms the ‘buddy system’, where each project is run by at least two members, but is opened-up to the rest of the group for ideas and criticisms at weekly ‘Pan-Assemble’ meetings. Each individual works on a freelance basis, keeping half the fee for the projects they do and putting the other half back into the collective, which pays for some members to do admin roles.

Assemble is so determined to keep its diverse structure because this has given it its edge, especially as it has moved into public-realm projects where understanding the needs of communities is essential. Non-architect members of the team undertake months-long consultations, working with local activist groups to get the public involved in testing ideas and even in construction.

“If you have people enthusiastic and involved from the beginning, and taking some ownership of it, then it means that they’re going to be happy with it,” points out Edgerley. And happy they are, not least in Toxteth, Liverpool, where Assemble’s work with the residents of Granby Four Streets housing estate brought their unexpected Turner Prize shortlisting.

The Toxteth project illustrates how far beyond the cosmetic Assemble are willing to go. They are, for instance, in the process of setting up a business manufacturing household goods, so embedding a legacy of craft and ensuring residents receive material benefits from the Turner nomination. “We’re just one part of the project,” says Edgerley. “Even though it’s an incredibly desolate area, the community spirit there is really amazing.”

This ability to nurture a sense of self-determination in communities is the key to Assemble’s success. They are not reluctant to concede power over the design process – that is their strategy. “It’s about asking for help as well,” says Leung. “In most projects it seems like the architect or designer is not in the best position to work out what all the answers are.”

Photography by Diogo Lopes

Discussion