Generation Risk

With employment prospects poor and career ladders going nowhere, it might just be better to invent yourself a job. Meet the ambitious millennials taking a new kind of career risk

In the spring of 2006 the youth of France took to the streets in the country’s largest protests since 1968. The demonstrations concerned a new employment contract law that opponents said would contribute to précarité – a pervasive sense of risk and uncertainty over future employment and material wellbeing. With youth unemployment then at a scandalising 23%, the young people of France were calling on the government to take action.

Fast forward to 2014. Youth unemployment in France is at 25%, and the government is doing what it can to help. But you don’t see the youth descending into the streets en masse to protest against the existential condition of risk. Having witnessed the financial crisis of 2008, the ensuing global recession and the general failure of governments and institutions everywhere to look out for them, today’s youth view risk simply as a fact of life, to be tolerated or even embraced.

To explore why this change is happening now, Protein conducted the Risk Survey at the end of last year, and found that millennials around the world are taking matters into their own hands and, in the process, reinventing work as we know it. The economic shift has coincided with shifts in values and technology, leading more millennials to spurn traditional jobs, take risks and make great leaps to start entirely new forms of career paths.

Lenna Boord, 37, Sydney

“I always had a little dream in my heart of one day opening a restaurant,” recalls LA-raised Lenna Boord. After realising that a couple of close friends in Sydney shared this ambition, the three of them decided to start a restaurant together in the city. The result was The Eathouse Diner.

The entrepreneurial plan was enabled, in part, by Boord’s on-going freelance stylist work, which continues to offer her an important financial safety net. She still books stylist jobs, thanks to a flexible shift pattern at the restaurant.

“You have to recognise what trade you carry with you when considering a move to a new country, so all my choices were driven by the realistic possibilities of continuing my career as a stylist within any new city,” she explains.

What’s more, even though the industries of styling and food on the surface appear quite separate, she was able to translate important skills from one to the other. “Managing constantly arising issues and resolving problems on the spot are skills I learned through the styling industry and was able to apply to the restaurant set-up,” she says.

Oliver Low, 30, London

Oliver Low, together with two colleagues, took an astonishing risk when they launched their own digital advertising agency, Breed & Craft. They had no experience of running a company and had to juggle their own incomes at the same time as growing the business. They knew little about tax and law – and had to learn quickly. And they did all this during the troubled economic period of 2011.

That said, while the founders had little experience, being relatively young meant they were free of the kind of responsibilities that might otherwise have held them back from starting a business. “Although it was definitely a risky move for us,” says Low, “the impact was minimal as none of us had mortgages or kids.”

While a lucky few, such as Mark Zuckerberg, hit the ground running fresh from graduation, Low says that a few initial years in a big firm, full of experienced individuals, only helps fuel the inner entrepreneur. “I was very lucky to have worked in inspiring companies and people were vital in the formation of our own company.” After all, Low and his partners would not have met if they’d not worked together previously.

An “often foolhardy” self-belief was important too, as without it, says Low, “you’ll only succumb to the numerous challenges and simply give up before you can establish yourself.”

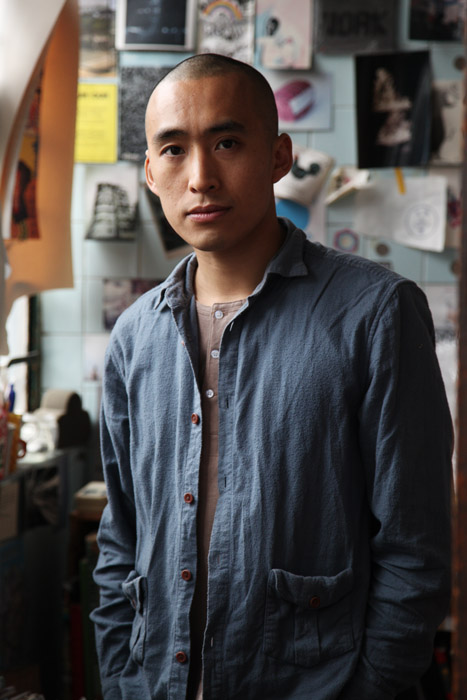

Michael Leung, 30, Hong Kong

Michael Leung is a Swiss army knife careerist and a very busy person. He’s a designer, a creative director, a visiting tutor at a design school, a beekeeper, a saltmaker, an urban farmer, he runs a café and, on Fridays, to round off his week, as if all that wasn’t busy enough already, he plays chess at a community arts space.

While Leung must have an incredibly well-organised diary, he is able to manage all these different roles because, first and foremost, he doesn’t see them as jobs. “They’re more like projects that I really enjoy being part of,” he explains. “Some are commercially sustainable, others aren’t – but I don’t mind.”

Through his varied projects, Leung has amassed a network so fruitful that one venture often leads to another. For example, his beekeeping, a project called HK Honey, involved a collaboration with the artist Glenn Eugen Ellingsen. The pair then also worked together to start HK Farm, an urban farming business, and Ellingsen played an instrumental role in helping to communicate the venture with his photography.

Leung believes in his generation’s questioning of ethics and systems. “It sounds quite abstract,” he says, “but I think a lot of people are now zooming out to allow them to zoom in on what’s important to them and question how to spend the hours between nine to five each day.”

Clara Aranovich, 28, Writer & Director

Clara Aranovich knew that a desk job wasn’t her thing, but the alternative – a career as a film writer and director – posed a big financial challenge. This all changed when she was approached by an experimental crowd-funding platform called Pave, which asked her to help headhunt the perfect aspiring filmmaker to showcase the service.

Intrigued, she took up the offer, but was in turn encouraged to apply for the filmmaker position herself. She leaped at the chance. “Voicing my own interest in applying for Pave funding was an exercise in having faith in myself, confidence and audacity – requisite qualities for a film director,” she says.

Her Pave profile successfully achieved funding, which she says was both unusual and greatly humbling. “That it could lead to a group backers – people I’d never met – coming together to invest in me as a person and filmmaker was shocking,” she says. “I’m still in disbelief.”

The funds have helped to pay for start-up costs, and in particular, her living costs – particularly useful when she took a lead producer role in an ultra-low- budget feature starring James Franco. “The experience was so invaluable and the project so beautiful, I couldn’t say no, but in other financial circumstances I would have had to,” says Aranovich.

Melissa Morris, 27, London

Melissa Morris appeared to have the dream career. She worked for a top business advisory firm with a client list of Fortune 500 companies. She travelled the world and worked with some of the smartest people on the planet.

But, for all its perks, the job didn’t have the allure of doing her own thing – in particular, seeing through an idea she’d had for a new technology start-up that would help people in the medical profession find jobs. “Once I got that idea, it was all I could think about – it was so distracting,” she says. “I had to leave.”

And that she did. But in starting up Network Locum she dived head-first into a sea of uncertainty: she found herself with no salary for two years and an increasingly uncompetitive CV as she struggled to make ends meet with ad-hoc freelance work. Nevertheless she battled though, encouraged by her supportive parents, as well as her previously honed abilities in financial modelling and presentations.

Now she is her own boss. But while this might sound like fun, she says, it actually means she works 24/7, “because you constantly think, sleep and dream it.”

Chris Herbert, 30, London

Having been a digital planner for over seven years, Chris Herbert had learned the ins and outs of Facebook and Twitter, so he was suitably equipped to turn an idea he’d had for a new phone app into reality in his spare time.

In fact, Herbert, normally risk- averse, only had the confidence to make Partify, an app that lets people announce parties and events to other nearby users, because of this experience. Any gaps in his knowledge, particularly technical, were easily filled through his strong network of friends and contacts.

Striking a balance between a hobby business and his digital planner day job isn’t easy – a constant problem for the digital tinkerers of this generation who routinely invent outside their nine-to- fives. Every extra moment can count. Two hours of daily commuting, for instance, became a quiet brainstorming session using his mobile. “The notes app on my phone has gradually become full of different ideas and lists,” he says.

Maintaining this productivity can also be a struggle, “particularly after a tough day when all you want to do is just switch off your brain,” says Herbert. “But doing your own thing can also be refreshing and give you a real sense of personal achievement.”

Hedi Jonsdottir, 33, London

Hedi Jónsdóttir was working every hour of the day to maintain both a full-time job in film production and a weekend passion for making handbags. But it was all too much and, eventually, something had to give.

“It was at that moment that I knew I had to make a decision,” says Jónsdóttir. “So I chose the route that made me happier.”

That route was the handbags, which saw her found her own label, Daughter of Jón. “Creating something aesthetic and useful makes me feel satisfied,” she says. “It’s like oiling my motor: it keeps my brain and my wellbeing going, which encourages me to stay motivated.”

She gained her technical abilities in design from her academic studies in fashion and tailoring, but much of her confidence came from knowledge gained in her former production career. “I learned a lot,” she explains. “The organisation behind big projects, working with a team, and above all, getting the business perspective of the product you are making and selling.”

There are perils to starting your own business, she warns: perfectionism being one. “I guess it’s because it feels so personal running your own thing,” she says. “It becomes hard to divide yourself and your work.”

Lower Loyalties

Much of this new risk-embracing attitude is the result of wider shifts in today’s economic environment. University graduates are not finding the job opportunities that their parents did, and those who do find traditional positions often no longer view them as long-term commitments.

Our Risk Survey found that millennials no longer consider it necessary to be tied to a single employer, with 84% of respondents stating they would rather have 10 jobs that lasted two years, than one job that lasted 20 years. “They saw their parents get laid off from corporations that they had devoted many years to,” says marketing expert and author Bill Connolly. “As a result, millennials don’t have loyalty to companies like their parents did.”

With employment prospects poor and career ladders going nowhere, it might just be better to invent yourself a job. Meet the ambitious millennials taking a new kind of career risk

In the spring of 2006 the youth of France took to the streets in the country’s largest protests since 1968. The demonstrations concerned a new employment contract law that opponents said would contribute to précarité – a pervasive sense of risk and uncertainty over future employment and material wellbeing. With youth unemployment then at a scandalising 23%, the young people of France were calling on the government to take action.

Fast forward to 2014. Youth unemployment in France is at 25%, and the government is doing

what it can to help. But you don’t see the youth descending into the streets en masse to protest against the existential condition of risk. Having witnessed the financial crisis of 2008, the ensuing global recession and the general failure of governments and institutions everywhere to look out for them, today’s youth view risk simply as a fact of life, to be tolerated or even embraced.

To explore why this change is happening now, Protein conducted the Risk Survey at the end of last year, and found that millennials around the world are taking matters into their own hands and, in the process, reinventing work as we know it. The economic shift has coincided with shifts in values and technology, leading more millennials to spurn traditional jobs, take risks and make great leaps to start entirely new forms of career paths.

Growing Up Slowly

Millennials are also waiting longer to settle down than previous generations. Student debt in the United States has ballooned to $1.2 trillion, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and shows no sign of decreasing.

“Young people face the prospect of taking on very large debts to complete their education and to pay back mortgages which may be five or six times their annual income rather than the 2.5 times annual income which was more typical of previous generations,” says Dr Karen Evans, a lecturer in sociology at the University of Liverpool.

A survey from the American Institute of CPAs found that student debt had caused 41% of respondents to delay saving for retirement, 29% to put off buying homes, and 15% to delay plans to marry. Little surprise that in 2011 the median age for first marriages reached historic highs in the United States, at 26.5 years for women and 28.7 years for men, according to the Pew Research Institute. Protein’s Risk Survey found that almost half, at 46%, of respondents said they didn’t really have any responsibilities at all. “There’s an expectation of having some time to figure things out on your own,” says Leslie Forman, an international career expert and entrepreneur based in Santiago, Chile. “What might be seen as an adult decision such as getting married or buying a house, I think for many people is seen as something you do after you launch your career.”

This delayed maturity has added what could almost be considered a new life stage for many millennials. Increasingly society understands that young people will have to grapple with financial struggles and devote time to career building after university and before they reach “true” adulthood.

Materialism to Meaning

Limited job opportunities and an inability to accumulate wealth are also behind a shift in values among millennial workers. “Meaning is the new money,” as James Wallman, author of the book Stuffocation, succinctly puts it. “Rather than show off through physical goods, like previous generations used to, they are expressing their identities and getting status through experiences they can share through social media.”

According to our Risk Survey, 62% of millennials would quit their current job tomorrow for a life- changing adventure. Such excursions are of course highly gratifying for the participants and also have the added benefit of providing exactly the sort of internet-facilitated personal status boost Wallman is talking about.

However, many millennials are also unwilling to accept that these two propositions are mutually exclusive. They want to see the world and do meaningful work at the same time. “They’re trying to balance their ambition and wanderlust, and the main desire that I’ve heard from many people is that they don’t want to settle for one or the other,” says Forman. Her contacts are determined to build international careers and aren’t satisfied with volunteering or teaching English long term.

Young Entrepreneurs

With less loyalty to traditional career ladders, and with more time and a greater emphasis on pursuing meaningful experiences, more people of this generation are instead choosing to make their own career paths. “Their mentality is that they have nothing to lose and everything to gain,” says Dan Schawbel, founder of Millennial Branding, a youth- oriented research and consulting firm. “That’s why many are choosing the entrepreneurial path at this particular stage in their life.”

Our Risk Survey found that a third of respondents in the study already run their own business. Other research released in June 2013 in the UK by The Prince’s Trust and RBS shows that 27% of unemployed young people would rather set up their own business than continue seeking jobs.

Others are taking on extra work simply to make ends meet or as a way of supporting themselves while they pursue a meaningful, albeit less well paid, full-time career. Although only 5% of UK youth are currently self-employed, a YouGov poll found that 43% had made money from some form of entrepreneurial activity, whether selling a product or freelancing a service.

Aside from these side hustles, many in this generation have simply quit to start again on their own: a plan B where entrepreneurship is seen as a way to design a lifestyle that is more conducive to meaningful experiences than the traditional nine- to-five grind. According to a study commissioned by Millennial Branding and oDesk, an online freelance job site, 57% of millennials who had left ‘regular jobs’ said they had quit in order to work for themselves, versus 42% of survey respondents overall. The most common reason respondents cited for quitting was freedom, at 69%. Comparing freelance work to “regular jobs”, 92% agreed that contract or freelance work allowed greater location flexibility than traditional employment.

There is even an admiration among this generation for those who make risky career moves. Inspired by the work icons of their generation – young, successful technology entrepreneurs such as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Tumblr’s David Karp – they respect peers who eschew traditional careers in favour of their own work paths. We found this in our Risk Survey: the vast majority, at 93%, in fact, said they would have more respect for a person if they quit a steady job in order to start their own business but failed, than had they simply stayed in that job and never taken the risk.

Tools of the Trade

Of course, the level of connectedness needed to sustain many freelance and independent careers, especially across continents, would not be possible without internet tools that we take for granted today. For a start, it’s easy to find ways to get the necessary funding to be independent. Crowd- sourcing networks such as Pave and Upstart

– similar in function to Kickstarter – help budding entrepreneurs to seek and find financial support for their careers and projects.

Then there are the social media and online collaborative working tools which began to reach maturity around the same time that the collapsing economy radically changed the way millennials think about careers. File transfer software such as WeTransfer and Dropbox has replaced heavy hard drives. Skype and Google Hangouts provide virtual means of hosting meetings. And cloud services such as Google Drive allow documents to be worked on by several people in real time.

Tools for crafting an online business have also become much more intuitive and easy to use

for non-specialists. Website builders such as Squarespace and e-commerce platforms like Shopify have lowered the technical and financial barriers to entry for would-be entrepreneurs hoping to sell their wares online. Integrating a PayPal button into a website isn’t the chore it used to be.

Social Following

Social media has also has created opportunities for freelancers and entrepreneurs to share their work with a much wider audience than was previously possible. Building an online network requires talent, time and persistence, but underemployed millennials have more time than money. Online social networking is essentially free, yet virtual contacts can serve as the sort of safety net that employers are no longer able to provide.

Austin Kleon, author of the new book Show Your Work!, puts it this way: “Imagine if your next boss didn’t have to read your résumé because he already reads your blog. Imagine losing your job but having a social network of people familiar with your work and ready to help you find a new one. Imagine turning a side project or a hobby into your profession because you had a following that could support you.”

In spite of uncertain prospects and the real possibility of failure, millennials are embracing risk and turning to entrepreneurship like no previous generation. According to our research, they consider risk challenging and exciting. In any case, risk is no longer the threat, as it was in 2006. It’s a fundamental part of millennials’ lives and careers, and they’re not waiting around for that to change.