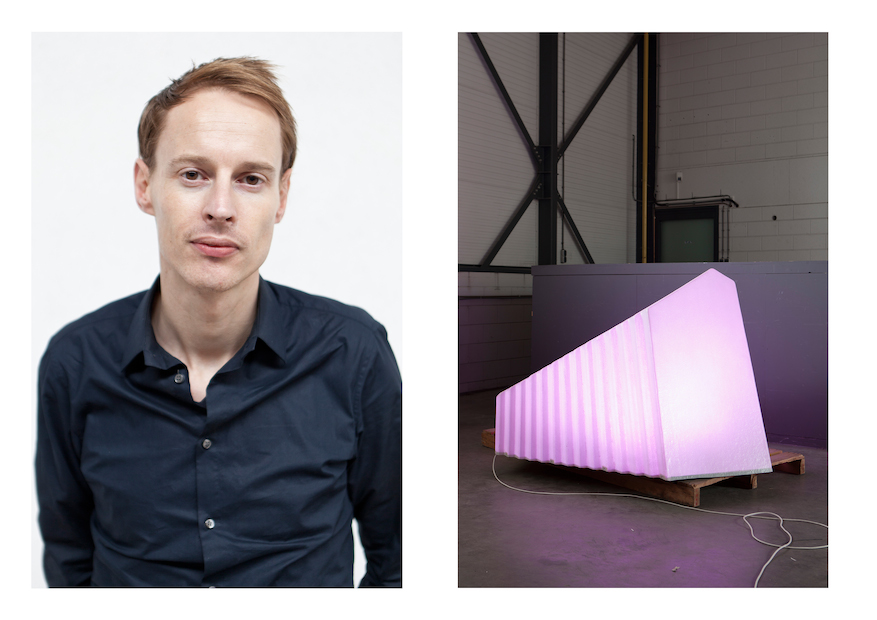

Daan Roosegaarde

Fresh from the pages of the latest issue of the Protein Journal, we speak to the Dutch innovator about the groundbreaking work his studio is doing and his optimism about the future.

Storytelling runs through Roosegaarde’s creations. Dune is one such project, in which interesting encounters between people and their environment is a highly tactile and poetic experience. This installation of digital ‘plants’ reacts through luminescence, sound and colour as people walk by. “It’s been interesting to see how people use the lights… making messages… writing letters… I even saw someone propose using the lights,” he explains. “I’d love to see social media take on these physical forms. How can we share stories outside the internet again? How can we enhance simple interactions using technology?”

It’s this mindset that has set Roosegaarde apart from other notables of his generation – as well as bagging him a clutch of deserved awards. He won the prestigious Dutch Design Award in 2009 and also scooped the Design for Asia Award in 2011. Roosegaarde, along with fellow designer Piet Hein Eek, is the current ambassador for Dutch Design Week, a job he does not take lightly. “My role as ambassador is to talk about process and not product,” he explains. “I don’t want to tell people how to use what I make: it’s up to them, but I do want to enhance lives.”

This ambassador recognises that the world is changing; that a focus on private ownership is no longer viable. His view is that the future lies in sharing and solving problems in a way that benefits whole populations. Little wonder, then, that he’s been asked to contribute to Waterschap, the government organisation that controls all the water in the Netherlands. The importance of this particular organisation cannot be underestimated – the future of the Netherlands depends on careful management of the network of dykes, dams and locks that keep the sea at bay from the low-lying nation – so a request for his involvement is high praise indeed for Roosegaarde.Further afield, he’s also been invited by the city of Beijing to address the smog that hovers like a chronic toxic halo over the Chinese capital, a brief that he responded to by proposing a giant balloon, of sorts, that creates an electromagnetic field and attracts polluting particles from the air.

Science and technology is vital to Roosegaarde’s practice, but does he ever worry that technology might one day become too powerful? “I do think that technology will become part of us,” he explains, “but I don’t mean this in an Orwellian scenario where technology dominates us… more in a way closer to Da Vinci’s practices, where technology can teach us to fly, show us how to cure ourselves and encourage buildings to live.” He continues: “The real challenge of the technological designer is to trigger the right scenario… make us aware of how the world is changing… and come up with valid proposals for the future. If we don’t listen to this way of being then technology will impose a real Orwellian danger, for sure.”

It is this understanding that technology can be our friend as well as being beautiful, personal and organic that has pushed Roosegaarde’s name to the forefront of modern technology design. “There is a new generation of designers that has emerged,” he explains. “Five years ago, companies would be purchasing objects from designers for their corporate lobbies. These days, businesses are looking for new answers and solutions. Designers are now here to convey the needs and dreams of the public to those who can realise them.”I think as humans we are always trying to customise the world around us – whether that is a natural world or an urban environment.[...] Updating reality always remains part of us. Like most innovators, Daan Roosegaarde is difficult to pigeonhole. Part architect and designer, part artist and philosopher, he is the charismatic founder of Studio Roosegaarde, the Dutch company whose high-tech projects look at the interactions between technology and humans, executed with poetic finesse.

The Canadian philosopher of communication theory Marshall McLuhan famously said, in reference to Buckminster Fuller’s infamous 1963 book: “There are no passengers on spaceship earth. We are all crew” – a saying that Roosegarde takes very seriously, suggesting that we all have our part to play in encouraging a more harmonious synergy between man and his environment.

“I think as humans we are always trying to customise the world around us – whether that is a natural world or an urban environment. As a boy you are building tree houses and dens; when you grow up you are constantly looking to reconstruct and develop your space. Updating reality always remains part of us,” explains Roosegaarde with mesmerising conviction. Of course, he aims to update this reality in a more drastic manner than the rest of us: Roosegaarde’s projects are groundbreaking in that he is exploring the dawn of a new nature, evolving from current technological innovations and creating interactive landscapes that instinctively respond to human kinetics and response.Half-Dutch, half-German Roosegaarde was 16 when he first visited the Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAi). Suitably inspired, he made the decision that his career would involve making things. A keen interest in the dynamics between scale, space, the body and its immediate environment led Daan to work on concepts of interactivity.

Fast-forward 17 years from his trip to NAi: Roosegaarde’s studio has outputted inventions as outlandish as Intimacy – a suit that becomes transparent if the wearer shows signs of not telling the truth – and as fun as the Sustainable Dance Floor – an interactive space that generates electricity through the act of dancing. But these are small scale in comparison with one of his latest projects: Smart Highway.

Smart Highway looks at amending one of the largest public spaces that design has not dealt with yet – the road. “When you look at our obsession with mobility and the ever-advancing technology of cars, it seems surprising that we rarely think about roads. These dictate much more of our lives than the vehicles themselves,” Roosegaarde says. “The Highway project aims to inject interest into roads again. How can we make our lives easier – safer – using new technologies such as paints that glow in the dark if it gets too cold, lights that are activated by the movement of cars, warnings built into the infrastructure?” What makes the Smart Highway all the more interesting is that not only are these ideas logical and practical, but they are totally possible: the technology exists and Roosegaarde wants to get it out there.

“I’ve always been more interested in reforming and not designing,” he explains. “There are plenty of people designing chairs and making things, practical things, but I prefer to focus on the existing and work out how to make it better.” Roosegaarde’s statement is as motivational as it is assuring, speaking a language that those outside of the design world can also understand. This is presumably why he was recently invited to become the first designer to appear on Zomergasten, a three-hour live interview programme now in its 25th year on Dutch television. Guests on the show are usually cherry picked from the worlds of politics, arts and academia, so it was high time that a designer was given attention on such a public forum. “The world is shifting from analogue to digital… Technology has become our second language, but that doesn’t mean we have to become machines – technology can make the world more friendly, more eco, more helpful, more beautiful!” he says.http://www.studioroosegaarde.net/