We meet the art world enfant terrible as he prepares to launch a ground-breaking new work splicing technology, performance and film

This summer, British multimedia artist Ed Atkins creates his most ambitious work to date. Performance Capture will see the artist delve even deeper into themes and subject matter that he is already familiar with: digital anonymity, identity, and how our relationship with the internet influences our construction of the self.

Atkins only graduated from Slade School of Fine Art a few years ago, but he’s already regarded as one of the most exciting artists of his generation. He’s 33 and based in London, although his work is exhibited around the globe at institutions such as MoMA in New York and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, as well as art fairs like the Istanbul Biennial. He’s highly regarded by art critics, and bucking the reclusive artist stereotype, Naomi Campbell recently threw a party in his honour. His work explores high definition video, intimacy, language, performance and avatars. Though he hates using the latter term, and wants to talk about issues that touch on far more. “I’m totally over this word avatar,” he says. “It works, but seldom captures the more interesting aspects of the process of working with a digital proxy, a surrogate. They are figures of fantasy who can undertake things I could never – that no-one could ever."

Where can one's inconsistent opinions, weird proclivities, fetishes, desires, hates, deep antagonisms, gut instincts be aired?

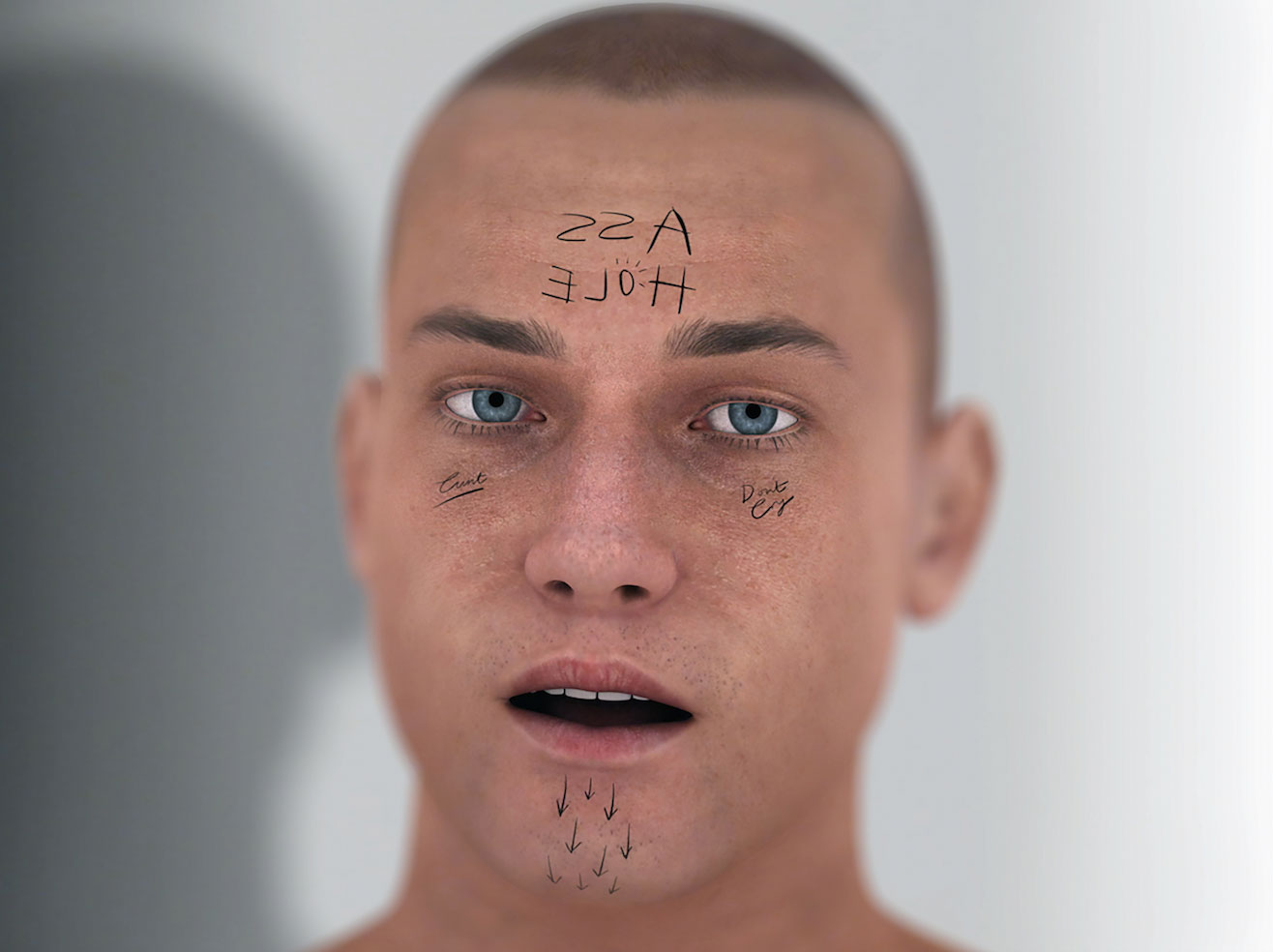

Performance Capture, presented at the Manchester International Festival, (MIF) and running from the 4th of July to 19th, will channel 120 of the festival’s performers and staff in a live CGI video, through a single, evolving avatar. Even though Performance Capture will last for 18 days, it’s far from being Atkins’s longest-running piece; www.80072745,a digital commission from Serpentine Galleries, began in autumn 2014. People who have signed up to the project will, for the next decade or so, receive occasional emails from the artist, written to look and feel like spam. The work echoes themes hinted at in Atkins’ Frieze 2011 film commission Delivery To The Following Recipient Failed Permanently in which the clarity of the message is secondary to exploring the medium viewers are looking at it through. In a post-Blair Witch scenario where an event is hinted at but never fully revealed, Atkins clashes an overwhelming spoken monologue with highly ambiguous visuals, such as the back of a head, to create a menacing vagueness. The purpose? To physically affect the audience, lose them in a foggy cloud of code, and get them to question the fragility of video as well as other digital work. No-One Is More “Work” Than Me (2014), presented at last year’s Art Basel, further explored the role of avatars. The piece employed an avatar on a screen, channelling a human controller, an actor sitting next to it – and making the actor seem almost less real than the avatar. Ribbons, one of Atkins’s best-known video works, which premiered at the Serpentine Sackler gallery in 2014, also made use of an avatar. A male figure had terms like FML, or WTF scrawled on its forehead; it smoked and drank and sang and talked, bellowing from various screens simultaneously, in a dark, off-kilter chorus that trolled viewers as they progressed around the gallery space.

Psychologists often consider the motives that might explain the way trolls behave online, which can sometimes be shockingly at odds with their real-world selves. The generally accepted theory is that the anonymity of the avatar doesn’t just remove inhibitions but allows users to take on an alternative personality. It’s no surprise, then, that Atkins sees avatars as “simply wearing a costume”.

“Like masks and disguises and the like, wearing a CG body affords a very different kind of performance, and makes a very different kind of identity possible,” he says. “The crimes one might get away with; the things you could say and be and do.” Avatars can offer a different kind of identity in an online world that is increasingly encouraging users to reveal their real identities, as sites link across various accounts for validity and supposed convenience. Where does Atkins stand on the anonymity offered by avatars? “Anonymity just gets less easy to spot,” he says. “Or more violently protected and often presumed criminal, rather than simply the exercising of a right. Like Twitter: who are these trolls? Certainly just people. How do these terrorists communicate? Via those last, vestigial places of anonymity. And after everything, the whole Snowden thing, it’s amazing that we still capitulate to some paranoiac spin we’re fed about openness, about security, protection, etcetera.” Where, he asks, can one risk misinterpretation? “Where can one’s inconsistent opinions, weird proclivities, fetishes, desires, hates, deep antagonisms, gut instincts be aired? Aired without fear of being shamed or ruined or whatever? I don’t know.”

Performance Capture isn’t so much seeking to explore what human beings are capable of when given the anonymity of an avatar; rather, it attempts to discover the humanity in the avatar itself. MIF’s artistic director Alex Poots recalls first meeting Atkins. “I remember going into the meetings thinking, ‘How can he help us evolve an idea to create a group show?’ and Ed, rather brilliantly, came up with what he described as a new type of portrait. He would create a portrait of artists and practitioners and technicians and all the people involved in the creation of new work; he would develop an avatar. It’s a group show of the festival, but using moving portraiture to create a portrait.”

Atkins himself describes Performance Capture as “a totally weird document of the festival in that performers and workers of every stripe from across the festival will take it in turns to don the tech and perform a chunk of my script.” Each performance will be consecutively rendered by a single figure, so that the final piece is a monologue, one figure soliloquising – but a figure comprised of hundreds of different performers.

“It creates the kind of world one might glimpse in a behind-the-scenes DVD extra,” he explains. “Performers will wear motion-capture suits; rooms will fill with overheating render farms; wireframe models will get fleshed and spackled with sweat effects, wind, CG props.” It’s an exhibition as well as a working studio, so it will be experienced as both production practicality and exhibition design. “Different aesthetics and their specific political citations will be conjured and confused.” Initially, there will the identity of the pre-fabricated avatar, which has programmed characteristics; and then there will be identities of all the participants being captured. The participants won’t be visible, although they might be identifiable by their physical idiosyncrasies such as the way they walk. Finally, there is the strange concept of the final avatar, which will be an amalgamation of all the captured performers.

At the core of Performance Capture is a thread of musings about identity that go back as far as ancient Greek times, when Aristotle’s Categories text set out to place every object of human apprehension into distinct categories. Atkins’ MIF piece playfully encourages us to question how we define human, computer, self and other, then asks how to draw a line of distinction between these categories. Despite being technically complex, Performance Capture – created in partnership with Manchester’s Studio Distract – is concerned with human identity, and has more in common with the practice of portraiture than it does with contemporary digital arts culture. This can also be said of the rest of Atkins’s work; while the medium he employs are often innovative and digital, they are used as tools to explore bigger ideas.

While many fashionable contemporary digital artists and digital curators can appear to occupy an impenetrably cool world, Atkins – concerned with higher matters – reaches out to touch on something universal, something accessible to even those without a grasp of the digital art scene. And his work is inspired by and addresses ideas from the online world. However, it resonates far beyond the insular bubble of digi-art cliques as it deals with issues that affect everyone, from the casual Googler and the brunch-sharing Instagramer to Anonymous activists – while exploring ideas about identity and humanity that transcend the purely digital.

http://edatkins.co.uk/

Originally printed in Protein Journal Issue #16