This is the kind of unerringly inspirational pronouncement that seems to define so much that Erin and Davey Spens do. For both them, their Boat Magazine, and its precursory design studio, it seems there are more important things on heaven and earth than an overflowing bank account. And in an age so often defined by the battle for profit and fiscal growth, it’s an attitude that is unsurprisingly compelling.

Nomadism is a term that gets bandied around pretty freely in travel publications. But when Boat Magazine defines itself as “a nomadic biannual” the phrase is used with somewhat greater weight.

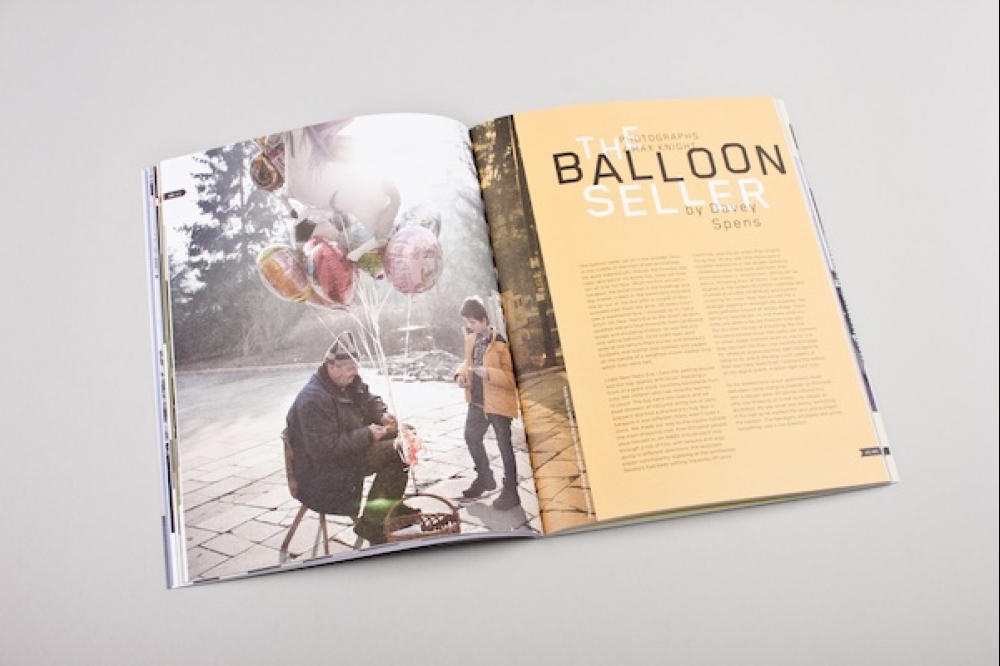

Twice a year, the husband and wife team (and, more recently, their young daughter) up sticks and move to a new city for a whole month. Every issue, a new city. Every city, an entire month. And from the house or apartment that they rent for themselves and the writers and photographers invited to join them, they work to dig beyond the usual tourist fodder and armchair-journalist stories. “Trying to give these cities which are so interesting and rich and chaotic more of a platform,” says Davey.There’s become this habit of arriving in a place to get what you came for and then leaving. Without ever stopping to listen. Without getting to know that city and letting it tell you its story. “What we try and do with the magazines," he continues, "is to go to a place that is misunderstood. When we Google Mapped Sarajevo for our first issue, we got a dot and it went no further than that. It was a telling observation that the internet is great at shining a spotlight on parts of the world that are tech-savvy and the rest are pushed further into the background.” Sarajevo, Detroit and London were the magazine’s first issues. Athens is underway. The list of future subjects is, in their own words, endless. The Middle East, Japan... the world is their literary bivalve mollusc.</p>

<p>On the one hand, Boat Magazine was evidently borne of the couple’s shared desire for adventure and a little, good old-fashioned job fulfilment. On the other, more practical, hand, it has also been beneficial for the magazine’s sister design studio, also called Boat. “As a design studio, we’re often asking clients to do brave things with their money,” Davey observes. “So we thought the best way of asking them to do something brave was to go a step further and do something ourselves – something that might not make any sense to do, but that we’re really proud of.”

The gambit seems to be paying off. The slew of “interesting conversations” they’ve been having as a result of their publication are already leading to fresh client projects, the new Temper Trap album artwork among them.

Even the origin of the ‘Boat’ name is in itself interesting. Before the magazine was even a glimmer in the pair’s editorial eye, it was chosen for the nascent design studio as a nod to their desire to remain small and nimble; crewed by never more than six or seven; flexible, fluid, and navigable on the changing tides of the modern economy. The very antithesis of the cumbersome, bureaucratic organisations upon which they had cut their respective creative teeth – Davey in the world of advertising, Erin in the world of fashion. “As someone who enjoys making things, spending 80% of your day in meetings doesn’t get the best out of people,” is how Erin puts it, no doubt to murmurs of agreement from many frustrated creatives.

When Erin and Davy speak about their magazine and its MO, it’s hard not to be caught by their trenchant frustration with the often vapid school of modern travel journalism.

“It just seems funny that sometimes cities can be consumed in such lazy ways,” explains Davey. By ‘funny’ he clearly means ‘infuriating'. “There’s become this habit of arriving in a place to get what you came for and then leaving. Without ever stopping to listen. Without getting to know that city and letting it tell you its story. Rather than you recycling the same 140 characters.”

“We have a general rule,” adds Erin, “that if you can find it on the first page of Google then you probably need to dig a bit deeper.”

It’s a technique central to countless forms of cultural fieldwork. This notion that it takes trust and acceptance and a real investment of time to break beyond the shield that we all naturally raise with strangers. “Trying to learn something,” as Davey puts it succinctly, “rather than telling people all the time.”

As an example of this ‘learning not telling,’ when the pair arrived in Sarajevo to begin work on the magazine’s inaugural issue, a taxi driver met them at the airport. During the long drive to what would be their home for the next month, he began pointing out all the war sites along the route: the scars and tortured memories burned into the landscape. Because that’s what people came to Sarajevo for. That’s what all the tourists wanted. ‘War tourists’ is what Erin calls them. “And whenever you approach a city that’s known for something awful in its past like that, there’s a kind of cynicism around your motives for being there. Tourism,” she sighs, “comes with a reputation.”

As well as allowing themselves the time to get to know their temporary hosts – to be known by them, to have their motives better understood – another point of difference is their endearing openness and willingness for adventure. Another way of putting that might be their charming proclivity to navigate by the seat of their proverbial undergarments.

So while the couple were being driven from the airport in Sarajevo – the house booked, the dead of winter curling around them, no writers or photographers actually confirmed, the first issue of this as yet undefined publication before them – they had only one name on their contact list. One name through which they hoped to unlock the door to an entire culture. A musician, as it happens. But they met him for a drink, and he opened up his little black book to them, and off they went. It’s a technique that they have come to rely on and relish since then: letting the city tell its own tale rather than applying their own preconceived editorial agenda.

“With Detroit it was easy in some ways,” Davey says, “because all we had to do was stop and listen. With London it was harder because we lived here.” This was the period when the 2012 Olympics were omnipresent. The city was being portrayed globally through endless imagery of pomp and ceremony and the unrelenting language of nationalistic purpose. “And we thought: that’s not our London. So we tried to go a little deeper and show some of the seven million faces that London has, rather than the one that was being presented to the world.” And write it they did. With an introduction by Nick Hornby to boot.

“There’s a general notion that print is dying,” says Davey. “There’s a new article published every six weeks that says so. But the depth you get with a magazine like ours is special. I was listening to Tim Hayward from Fire and Knives talking the other week, and he said that his ‘environmental policy’ is simply to make a product that doesn’t get thrown away. And there’s something to that... We want to make something that has a longevity beyond just being a magazine.”

With every issue, their global sales shift around the world, evidently engaging with the locals whose stories they tell as much as any foreign audience. Something like 80% of the sales for the Detroit issue came from the U.S. alone, for example. And a core reason for this must surely be the magazine’s accessibility: that balance between macro and micro, between news stories and long- form travel articles, between them and us.

But also, it’s hard to believe that its success doesn’t owe something to their contagious optimism, a literary frontierism that is joyous and endearing. Take Erin and Davey’s approach to growth: “As a studio you can get stuck in a rut by doing the same thing over and over.” There can’t be a creative on Earth who doesn’t agree with that. “By picking ourselves up and moving to a different environment entirely,” Davey continues, “we force ourselves to be in some uncomfortable situations. Our story as a studio is that the only real way to grow is to overstretch yourself. It’s hard sometimes to recognise the signs of growth. But when you’ve overstretched your credit card and you can’t pay for the postage for your magazines, you know you’re probably growing as fast as you can. And that’s alright.”

And with that, we defy you not to feel that tingle of contagious inspiration; the urge to book yourself a ticket to such an ‘uncomfortable situation’, ears open and ready to listen.

http://www.boat-mag.com