Back in 2010 Blaise Bellville live streamed a DJ set from a room in Hackney. Now he's in charge of Boiler Room, a global platform rocking the foundations of the music industry.

Wapping is a disconcertingly quiet residential area built around the old tobacco docks of east London. These days it’s home to the apartments of city boys, a few old pubs and not much else. It certainly doesn’t seem the sort of place where one of the most respected brands in global underground music would be based.

But Boiler Room has just relocated to a riverside townhouse here. The company’s founder, Blaise Bellville, shows me round his newly converted office space, packed with video editors, bookers and journalists, most of them identical-looking in over-sized white T-shirts, woollen beanies and black jeans – the look of the British clubber. Upstairs there is a purpose-built studio with soundproofing foam on the windows so as not to disturb the neighbours. Bellville boils the kettle in the kitchen and then, 20 seconds into the boil, says “Actually, shall we go to the pub?” and so we relocate three metres to the pub next door. I start to see why he chose Wapping.

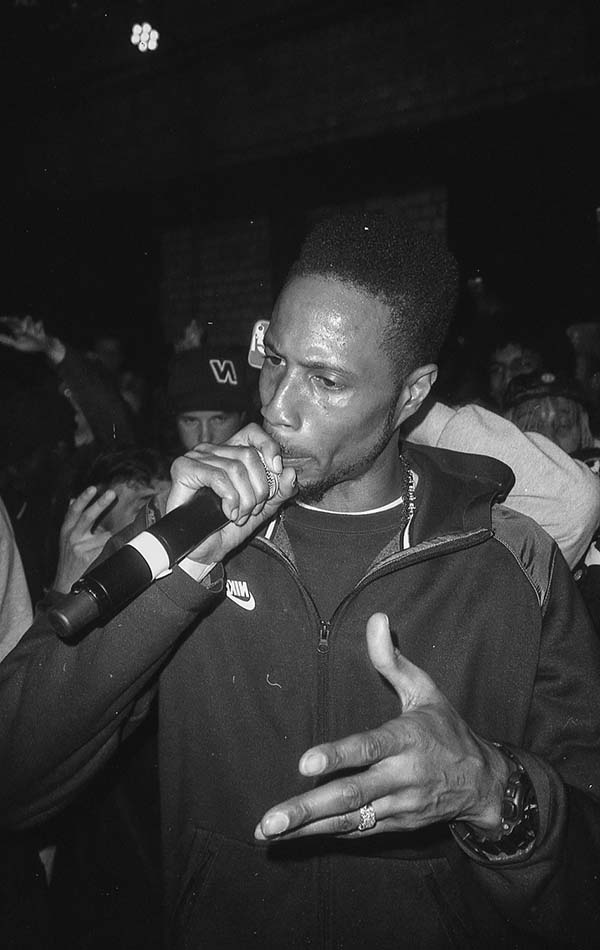

Boiler Room started in 2010, based on a concept that sounds both obvious and counter-intuitive: the livestreaming of DJ sets on the internet. Its earliest shows were low-quality Ustreams of a few of Bellville’s mates hanging around drinking Red Stripe while a DJ played. It was the exact opposite to the viral short-form video content that was assumed to be the only way to thrive online. But Boiler Room picked up a loyal following, particularly of electronic music fans, who congregate in a chat window below the stream. Since then Boiler Room has gone global, putting on shows across the world from Tel Aviv to Miami to Punta del Este to Johannesburg. DJ sets are still its bread and butter but it now incorporates live performances in a range of underground genres, and last year broadcast a series of concerts by avant-garde classical performers.

“Boiler Room was never an idea in such a decided way,” recalls Bellville, when I give him my precis of the way things started. “I didn’t think that we would start streaming DJ sets, create a website and then start going to other genres or whatever. I wanted to do a mixtape site – recording it on video just seemed liked the easiest way to do that. I woke up the next morning after that and thought that video thing was quite cool and there were a lot of people chatting online, and that shaped what I did the next week. By week 10 we’d totally departed from the original thing. Had I spent six months thinking about a plan around this, I never would have done it.”

Each week Boiler Room was broadcast from a back office in a building Bellville was renting as office space. Sets would stream for a few hours on Tuesday nights. There were no staff, there was no plan, Bellville would “be there till the early hours, picking up cigarette butts.” Yet within a few months Boiler Room had gone from “the limited clique of people I knew” to a mini-phenomenon among club kids. The (then) cutting-edge post-dubstep sound that was taking over London clubs found its home at Boiler Room, with the likes of Jamie XX, Mount Kimbie and SBTRKT playing sets early on. When Boiler Room had just started, it featured a PA from an unknown vocalist called Jessie Ware, as well as one of the only sets from the late DJ Rashad, the golden boy of the Chicago footwork scene. What surprised Bellville was not that these streams were popular, but the people they were popular with. “We started seeing people from tiny places around the world joining. That really started to shape our ideas some more. It was kind of like a keyhole into the London scene.”

Boiler Room’s story follows the same basic structure as that of most youth-focused companies trading on cool: it started off as a fun thing for a few friends, then other people got interested so it expanded. But in most cases, expansion means reaching beyond that cool crowd, opening up to the masses while somehow holding on to that initial appeal. This, of course, rarely works: when a hot new spot opens up in east London, it’s where all the cool kids hang out for six months, then it ends up in Time Out, gets too busy and soon the hipsters have moved on somewhere else.

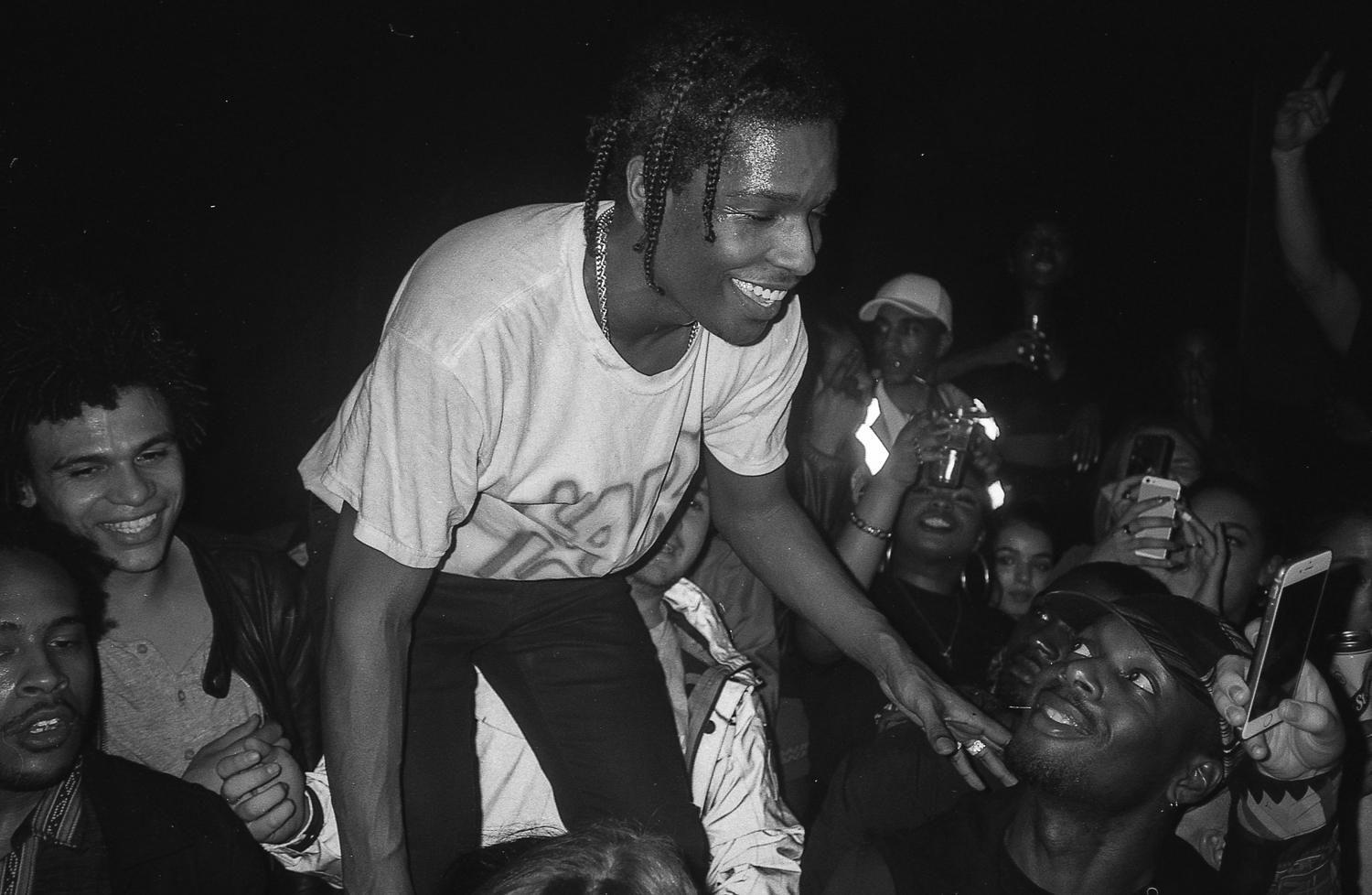

But Boiler Room remains well-respected by everyone from students to nerdy 30-somethings, and especially by the producers and artists on the cutting edge of emerging genres. It continues to book the very best DJs and rappers, often years before they’re recognised by other outlets, and although it’s gone for the occasional bigger name, this is hardly Top of the Pops: the most populist Boiler Room has probably ever got is when a few of A$AP Mob showed up to a show in April, or when Thom Yorke played a DJ set of obscure Africa Hitech remixes.

Instead, it has slowly expanded into other niche genres of music, each show bringing in a different group of people, slowly increasing the Boiler Room audience. The first step was going to Berlin and trying out the same theory with the techno scene there. Sure enough, hundreds of thousands of people tuned in to the shows. The Berlin scene dwarfed what Boiler Room was were doing in London. Yet even with those successes, it still seems surprising that today Boiler Room, with its highly niche content, has more than a million Facebook likes, and over 170 million YouTube views. How can there be that much interest in such specialist music?

“When a specialist genre emerges, it emerges in the club but it also gathers around the world. That’s our modern movement. Back in the day, people used to go to Woodstock and everyone bemoans that we don’t have that, but we do have this digital movement in that you can share a moment anywhere around the world,” says Bellville. “What we found is that the people watching the shows were usually not from London – they’re from all over the world. They use it as a way of hanging out with other people that are into their own specialist shared subject. A scene is never just ‘where it happens’, and Boiler Room heavily plays into that.” Perhaps Boiler Room was also aided by a general lack of on-the-ground enthusiasm for underground music. In London, clubs that deal with specialist music are closing all the time and the ones that keep going tend to struggle without big names. Take Boxed, a night that deals in the experimental, future-facing new wave of grime that has been covered everywhere from Fader to the Guardian. Online, there’s a lot of buzz, but the night itself is often not that busy – it would be hard to call it the centre of a movement.

Bellville agrees. “That’s the thing. Before, if you were running a Boxed or something, there would be screaming fans and thousands of people outside your club. The reality of the modern-day movement is that, yeah, you’re recognised, but it’s nerds from all around the world who make up your audience. At Boiler Room, when we talk about communities, we’re talking about 50 or 5,000 or 20,000. Sometimes I’ll look at a stream with a small artist and I’ll tell them they had 10,000 people watching and they seem kind of underwhelmed, but that’s like the biggest venue they’re going to play in real life. These people have chosen to tune in at a specific time to watch your show and those are the people who would buy your tickets.”

Everything Boiler Room does is funded by a small fraction of its shows; Bellville reckons about 5%, specifically the ones that involve some kind of brand partnership. It has worked extensively with Ray-Ban, Adidas, Vans, Red Bull and a host of others. “The way we do it is generally looking for artists who want to get a project off the ground – something ambitious, not just booking a DJ line-up but something more creative, like when we did a Hudson Mohawke show with kabuki theatre and samurai displays. We’ll talk with partners who share that vision and see the value of very directly connecting with our fans.”

The power of emerging music is the hundreds of millions of fans around the world So what is the future for a company that refuses to engage with the mainstream? Is there a limit to what Boiler Room is capable of? It seems as though two quite different directions are planned, perhaps a reflection of Bellville’s “let’s see what sticks” attitude. The first is to start making different kinds of content.

“There’s a load of new things we want to experiment with, beyond the performance. In order to do that, in the next three months, we’re dramatically reducing our output of event-based broadcasts and developing new formats,” says Bellville. “We did 279 shows last year, which is ridiculous. Keeping people’s concentration is really important to us, and I think that relies on not pelting your audience too much. So we want to rationalise the opportunities. If some tiny, super-specialist, weird-as-fuck label comes along and we love them and want to do something with them, we need to be able to do that.”

Boiler Room’s new strands include In Stereo, where bands play a 60-minute session that ends up looking like a flashy music video, and Collections, where musicians or specialist record collectors talk about the highlights of their collection. These are long-form, niche content with music at their heart. And then there’s new arts strand Dearth, created by Guy Gormley, artist, photographer and son of legendary sculptor Antony Gormley.

“The idea of Dearth is to open up Boiler Room to interventions from artists and support those projects,” Gormley explains. “The next artist to contribute to Dearth is Mark Leckey – he’s an important artist for us because he kind of pre-empted YouTube, and has made work in relation to dance music and its history, which is what Boiler Room is directly concerned with now. It’s hard to say what will come after Dearth at this stage. I think people are still just cottoning on to it as we consciously introduced it with very little noise, and we are still realising what its potential is, but I’m open to being led where it takes us.”

The biggest plans though, involve expanding the company beyond a single brand. This is an awkward issue for Bellville, but, as he puts it, there are some genres of music they’d really like to cover but are unable to, for credibility’s sake. “We talk to a multitude of different musical tastes when we’re booking people, but all falls under what could basically be called ‘our world’,” he explains. “Yes, our world dips into almost every musical genre, from classical to techno to grime. But it’s really about how good that music is in a slightly nerdy, ‘above everyone else’ sense. The point I’m getting towards is that there are huge audiences out there that would consider themselves underground but we just don’t deem good enough. It’s a horrible thing to say, but it’s true.”

Bellville lists a few untapped markets he’d like to get into but can’t: the hip-hop and funk of favelas in Brazil, unsigned road-rappers in the north of England, the huge electronic music scene in India. South African house is another example. “95% of the country listens to house music and a lot of it is pretty underground. If we wanted to do a Boiler Room with house music in South Africa it would be a massive smash hit. It’s a huge and exciting scene and an audience that I really respect. The only thing stopping us is that a lot of our global audience wouldn’t consider it developed. If you take the most emerging South African house music out of context from the audience where it’s valid and you fly them to east London, some people would think, ‘What the fuck is this?’”

So what’s the answer? “I see the future of Boiler Room as a lead brand with other brands that are part of it,” says Bellville. “I would create a brand that speaks completely unashamedly and exclusively to the emerging music market in South Africa, without being worried about what’s cool in Dalston. I think you could do that with five different musical markets around the world, and then you’re not batting anyone away. When you talk about Boiler Room celebrating the world’s best music, you’re really just talking about one very developed first-world site. The power of emerging music is the hundreds of millions of fans around the whole world. Most kids in India could give two fucks about what Pitchfork are writing about.”

Boiler Room’s website already lists more than 40 cities where it has held shows. But that seems to be just the beginning. Boiler Room is attempting to connect the underground in five continents into a digital community; to turn an entire global culture that previously only existed in fleeting late-night moments of real-life interaction with a few people into something that can be documented for a dispersed but dedicated community. For a company based around an almost laughably simple premise, what Boiler Room is actually trying to achieve is hugely ambitious.

Originally printed in Protein Journal Issue #16. Photography by Vivek Vadoliya

Discussion