It would be an understatement to say that opinions on the matter are divided. What’s more, defining subcultures has always been a complicated task. After Shang Salah sowed the SEED in our Contributors Forum, we asked five other members to share what subcultures mean to them and which ones, if any, they’re currently into.

Shang Salah

As a young creative, I’ve read too many articles pitying the current youth for their lack of subcultures. It’s made me question whether subcultures have truly died, or whether we’ve replaced them with something else. More specifically, have we swapped them for identity politics or identity-based groups? Or, on a more superficial level, have they been replaced with aesthetics?

Personally, I find it hard to believe that subcultures are dead. Take, for example, the shift from being part of a socialist punk group to now identifying with a creative Middle Eastern women’s group. The underrepresented are responding to decades of being unheard, and are prioritising the act of coming together through shared identity. We’re also living in an increasingly hyper-individualised society, so the more niche or specific a group’s description, the more likely we are to gravitate towards it.

That said, whenever I read about the subcultures of the ’70s or ’90s, it seems the real difference between then and now isn’t the youth’s lack of ideological stances, but the absence of spaces for them to gather and engage in meaningful discussions. I live in London, where even a simple coffee costs a lot of money – let alone the price of securing a space for regular meet-ups. As a result, we’ve adapted and now engage with our communities primarily online, through forums or social media. Many of my friends argue that this is the main reason why subcultures will never be what they once were. Another argument is that for many, it’s simply unaffordable to practice their art or creativity without commodifying it. Starting a band for fun seems impossible nowadays – the band needs to fit into a bigger plan of becoming a professional musician. We simply don’t have the luxury of time to pursue hobbies for the sake of the hobby.

Are subcultures truly long gone, or have we simply rebranded them? Personally, I lean towards the latter. I believe we’re more connected to our dimensionality now than ever before, with individuals able to be part of multiple communities – both superficial and profound – at the same time, often prioritising those that resonate with our identity. But the frustrating reality is that it’s prohibitively expensive to physically be part of a group on the regular, so instead, we engage online. That, I think, has become the new home for subcultures.

Shang Salah is a director, producer, video artist and researcher.

Jack Stanley

I think subcultures will always exist, they’re just going to change and shift a lot quicker than they used to. The interesting thing is that it feels like the age of dominant subcultures is over, and there’s a way in which all of these things can be huge and completely separate. I’ve been really interested in the hardcore crossover into mainstream, which I think a lot of people (myself included) didn’t expect.

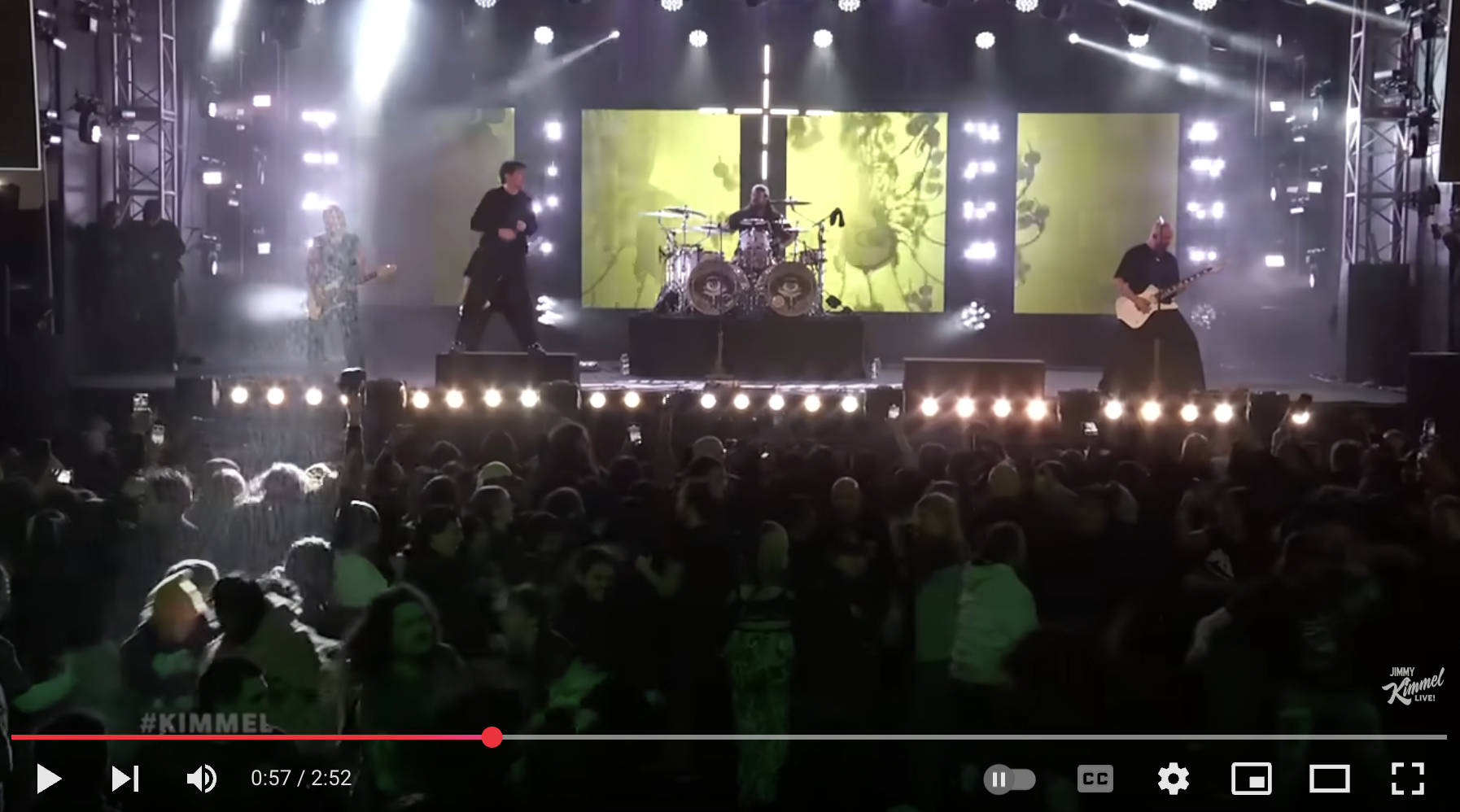

You’ve had Turnstile conquering the world a few years ago, Knocked Loose on Jimmy Kimmel and High Vis becoming the biggest band in the country. I think it’s interesting to see the extent to which a subculture can crossover, as well as what it loses and what it gains along the way. Hopefully the values and practices associated with the culture will survive as it gets bigger and bigger.

Jack Stanley is a writer, strategist and anthropologist; his newsletter, Heavy Weather, is about brands and the way they work.

Joanna Lowry

Not to be a stickler for semantics, but it really depends on how we define “subculture”. The sociologist Dick Hebdige defined a subculture as a group that emerges in response to societal norms, expressing resistance and identity through distinct styles, practices and symbols. By this definition, subcultures are about subverting the dominant paradigm.

While there are loads of interesting, niche communities online, I’d question whether we have a genuine, thriving counterculture right now, as many of these communities seem so intertwined with capitalism. I don’t think TikTok aesthetics or “cores” really qualify as subcultures. That said, I’m quite enjoying all the coquette, Sandy Liang-esque vibes circulating at the moment. And as someone who wore a lot of eyeliner in the noughties, I’m looking forward to seeing the exhibition I’m Not Okay: An Emo Retrospective, which was curated by the Museum of Youth Culture.

Joanna Lowry is Head of Strategy at Protein AGENCY.

Charlie Robin Jones

There’s no singular subculture I’m into at the moment – I’m a 40-year-old classical millennial that, despite working for youth media brands in the past, has never had the singularity or swagger to join one, and certainly isn’t going to start now. However, I’m incredibly into the fact that subcultures... seem to be... back?

For most of this century, and certainly since the great crash in 2008, there was a dominant narrative that subcultures were extinct. Mods, rockers, punks, ravers – all gone, washed away with the other violent, bright extremities of the 20th century. In their place came normcore – the closest thing my generation had to a unified aesthetic, or set of cultural touchpoints – which, really, was a negation of subculture, from original to execution. No change of dress needed between the club and the office, nothing that different between you, me, or the people over there.

But now, weirdly, I can discern differences? I feel the need to add a doubting question mark, so marked is the change, but one can feel it: not just a subtle change in affect or emphasis, but wholescale moods. For the first time in a long time, one can make a prediction about what someone listens to on the basis of their clothes. You can feel what Chantal Mouffe called an agonism in the air – people with different politics, different worldviews, different media environments, different platforms, different aesthetic codes, all playing out on the same planes that good old 20th century subcultures used to. Music is back. Style is back. Violence is back, too. The vibes have shifted, and it’s a new decade now.

Charlie Robin Jones is a culture writer, editor and strategist.

Joe Muggs

Subcultures are less instantly visible now than in the 20th century, when they revolved around groups of people meeting in specific localities, and perhaps they’re more fluid now, but in fact they’ve always been fluid, contingent, intersectional and multiple in their identities. We need to move away from the 20th century gatekeeper model of defining them, and see all discussion about them as negotiating their nature – because every discussion about them adds to and alters what they are, and also adds to and alters the question of whose opinions matter in defining them. Are they defined purely by the participants, casual observers, journalists, brands, historians in retrospect?

This, too, is a constantly contingent and shifting issue. So, yes, it’s complicated! But subculture absolutely still exists and is vital for both participants and for what it incubates and returns to wider, deeper cultural streams.

One other question that I find underrepresented in the discourse, whether that’s journalistic, academic or whatever, is the personal realities of time. Right back in the early 00s when I started writing professionally, there was a received wisdom that subculture was over even then because instant availability via Napster and other internet access was going to flatten everything out. But, in fact, real, geographic cultures were emerging; in the UK music world it was grime, dubstep, what we now call “indie sleaze”, the nu-folk movement… and as I documented these I came up with a phrase:

“No matter how fast information travels, it still takes three years to get from being 15 to being 18 – culture still changes at the speed of life”

That especially applies to cultural things that require skill-learning – for example, playing an instrument, which is why the new generation multicultural jazz explosion of the past decade has been so vital. The process of learning, craft and being in rooms together anchors that culture in space and time, right? There’s stuff happening that can never be co-opted, whether Boiler Room videos or TikTok trends or AI – you’re either there or you’re not. And this also applies to online cultures, which are temporal because they’re about unfolding chats, or being the first to experience a sound or video or piece of news.

Joe Muggs is a culture writer and copywriter, and runs his own blog called Very Very Much.

So, what do you folks think? Have subcultures been subsumed by corporations? Have they been replaced with individuals cycling through trends? Or have they evolved and are multiplying rapidly, ushering in a new golden era?

Answers in the comments below or become a Contributor to share your thoughts and plant your own SEEDS in our digital garden.

| SEED | #8292 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 06.02.25 |

| PLANTED BY | PROTEIN |

| CONTRIBUTORS | CHARLIE ROBIN JONES, JOANNA LOWRY, JOE MUGGS, SHANG SALAH, JACK STANLEY |

Discussion